2006年以降、マイケル・アンソニーは、マンハッタンのグラマシー・タバーンに徹底した季節性をもたらしてきた。日本とフランスで培った経験を融合させながら、彼自身が「コンテンポラリー・アメリカン・クッキング」と呼ぶ、新たな料理の指針を打ち立てている。

Profile

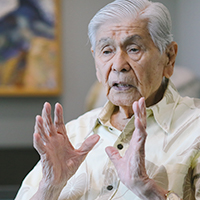

第71回 Michael Anthony()

グラマシー・タバーン エグゼクティブシェフ

マイケル・アンソニーは、Gramercy Tavern のエグゼクティブシェフ兼パートナーであり、同時に Whitney Museum of American Art 内の Untitled および Studio Cafe のエグゼクティブシェフ兼マネージング・ディレクターを務めている。2006年にグラマシー・タバーンのエグゼクティブシェフに就任。彼の指揮のもと、同店は『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』三つ星評価(2007年)を獲得し、ジェームズ・ビアード賞「最優秀レストラン」(2008年)および「ベスト・シェフ:ニューヨーク市」(2012年)を受賞した。2015年には全米規模の評価となるジェームズ・ビアード賞「アウトスタンディング・シェフ」を受賞。著書『V is for Vegetables』は、2015年ジェームズ・ビアード賞「最優秀野菜料理書」を受賞している。

コンテンポラリー・アメリカン・クッキングとは何か

私はこれまでずっと、ニューヨーク、そしてアメリカという国で暮らし、働けていることをとても幸運だと感じてきました。日本をはじめ、アメリカ国外へ行くと、人から「どんな料理をしているのですか?」と聞かれることがあります。そのとき私はこう答えます。「アメリカのレストランで働いていて、コンテンポラリー・アメリカン・クッキングをやっています」と。するとたいてい、相手はきょとんとした表情になります。

アメリカに住んでいるという文脈を離れると、コンテンポラリー・アメリカン・クッキングとは何かを、まだ誰もきちんと理解していません。それが何を目指し、何によって定義され、他の料理スタイルと何が違うのか。けれど私は、アメリカ料理はいま、すでに幼年期を終えた段階に来ていると思っています。この段階を正確にどう呼ぶべきかは分かりませんが、あえて言うなら思春期でしょう。面白くなるために、どのようにルールを壊すべきかを模索している段階です。思春期の若者と同じように、反抗的な者もいればそうでない者もいますが、皆が自分自身を見つけようとしています。「自分とは何者なのか」「何になりたいのか」という問いを、自らに投げかけているのです。

人々はいま、私たちに対してより厳しい問いを投げかけるようになっています。なぜなら、すでに初期の“手品”のようなものは見尽くされ、それが単に新しいだけではなく、まったく前例のないものでもないと理解されてきたからです。そこには競争意識があります。しかも競争は、ニューヨークやアメリカ国内にとどまりません。世界は本当に情報を共有するようになりました。若い料理人たちは世界中を旅し、これまでにないレベルで知識や経験を共有しています。かつては公式な徒弟制度や料理・文化の内輪の知識において、非常に閉鎖的だった日本でさえ、その状況は変わりました。以前の日本の料理人たちは、世界中のシェフと会うこと自体は歓迎していましたが、「外部の人間には日本のおもてなしの本質は理解できない」という感覚があり、その交流を必ずしも重要なものとは捉えていませんでした。ファッションやアートなど他の分野でも同じかは分かりませんが、料理の世界では特に顕著でした。

正直に言えば、私自身も、茶道が日本のおもてなしの中でどのような役割を果たしているのか、また季節料理や懐石の伝統がどのように進化してきたのかを理解していなかった側の人間でした。かなり大きなくくりの話ではありますが、ここ10年、15年、20年ほどで、日本は料理の分野において大きく開かれ、その料理が世界のファインダイニングの捉え方に与えてきた計り知れない影響が、ようやく広く認識されるようになったと思います。その影響は、フランス、イタリア、スペインの偉大なシェフたちを通して伝えられてきましたが、今やそれは、これまで以上に世界を魅了しています。

だからこそ私は、この一連のプロセスは、アメリカの料理人にとって大きな強みになり得ると考えています。文化や料理の歴史と進化を丁寧に学び、意識的かつ規律を持って向き合うこと。そして同時に、自分自身のユニークな声を自由に定義すること。その両方が必要です。だからこそ、私たちは今、とても刺激的な分岐点に立っていると感じています。

伝統をつくり、そして壊す

温故知新 ――これは「古きを学び、新しきを生み出す」という意味の日本語です。先人の仕事を尊重しながら、新しいことを始めるという考え方です。 この温故知新という概念はとても興味深いものですが、正直に言って、アメリカ人はあまり得意ではありません。ニューヨークを見れば分かるように、ここに住む人々は制度的な記憶がとても短いのです。私がキャリアやニューヨークの食文化に影響を与えたシェフの名前を挙げても、多くの若者はその名前を聞いたことがありません。キッチンで一緒に働いている人たちでさえ、知らないことがあるほどです。

それが現実です。ある意味では、日本の生活に見られる表層的な側面にも、同じものを感じます。たとえば日本では、本来であれば適切なメンテナンスをすれば25年、30年と使える冷蔵庫であっても、新しい機能が出ると最新モデルに買い替える家庭が多い。ニューヨークではそれが建物や不動産に表れます。古いものはすぐに壊され、そこに何があったのかを示すプレートが壁にあっても、ほとんど見過ごされます。そして残念ながら、私たちは家族の歴史に対しても同じような態度を取っています。私の父方の家系はイタリア系アメリカ人ですが、祖父母はアメリカ生まれで、第一世代・第二世代のイタリア移民に囲まれた労働者階級のコミュニティで暮らしていました。私は曾祖父母に会ったことがなく、名前すらすべては知りません。彼らがどんな人間だったのかも、ほとんど知りません。確かに存在していたことは分かっていますが、それ以上のことはほとんど知らないのです。それが、たった四世代前の話です。

一方で、最後に日本を訪れたとき、私は京都で14代続く料理人に出会いました。血縁でつながった人々が、代々同じ創造的な営みにエネルギーを注ぎ続けてきたという事実は、ほとんど理解を超えるものです。実に驚異的です。人生や相対的な時間軸について語り始めると、正直に言って、アメリカ人はそれを理解するのがとても苦手です。ほとんど実感がありません。歴史を理解しない者は、それを繰り返す運命にあると言われます。私たちは、歴史そのもの、そして自分たち自身の歴史の価値を過小評価してきた、重要な転換点に来ているのかもしれません。私たちは、自分たちの経験から学ぶことに失敗してきたのです。

人生には、自分の道を自由に選ぶ個人の自由と、レガシーを受け継ぐこととの間に、バランスがあると思います。どちらにも価値があり、その間にこそ“魔法”があるのかもしれません。正直に言えば、私は自分の人生をとても幸運だと感じています。私の世代は、家族や国家に縛られていないがゆえに、「自分は何をしたいのか」を問い続けなければならないという、贅沢さと同時に呪いのようなものを背負ってきました。人種的偏見が残っているとはいえ、いま私たちは、かつてないほど多くの可能性が開かれた世界に生きています。世界中の人々が、過去には存在しなかったチャンスにアクセスできる時代です。母は料理上手でしたが、家族の誰一人として、私をシェフの道へ導いた人はいませんでした。伝統に必ずしも縛られなくてよい、という考え方には、非常に大きな力と解放感があります。良いセンス――これは主観的な言葉ですが――を持って前に進むことができれば、その自由さを武器に、面白いことができるのです。

アメリカ人としての声を見つける

私は大学でフランス語を専攻し、日本語を副専攻しました。日本語を学ぼうと思ったきっかけは、純粋に言語への愛情からでした。フランスで自転車旅行をしていたとき、5日間一緒に走った2人の日本人と出会い、その旅の最中に日本語を学びました。その後、大学に戻って日本語の副専攻を修了し、卒業したその日に日本へ渡りました。言語を実践したかったのですが、食はそのための最高の手段でした。とても親切な人が経営するパン屋で早朝から働き、真剣に働くならパン作りを教えてくれるという条件で雇ってもらいました。それは、自分が暮らす町と深くつながる、目を開かされるような体験でした。

やがて私は、インターナショナル・トリビューン紙の料理批評家に手紙を書き、日本に住んでおり、辻調理師専門学校への進学を考えていると伝えました。返事をもらい、六本木でレストランを経営していた島静代さんを紹介されました。彼女の人生は、それ自体が非常に刺激的な物語です。彼女はフランスで著名なシェフのもと、あらゆる困難と闘いながら修業を成し遂げました。80年代に東京へ戻り、当時はまだ静かな街だった六本木で店を開きました。今の六本木ミッドタウンタワーの、文字通り向かい側です。静代さんは、フランスと日本を融合させた、魅力的で親密な料理表現をしていましたが、その一方で非常に厳しい修業を積んできたため、私にも同じような試練を課しました。

修業中、私は何度も自信を失いました。時には、「これはやりすぎではないか、殺されるのではないか」と思ったほどです。しかし耐え抜き、ある日ついに彼女はこう言いました。「私が知っていることはすべて教えた。だから次へ進みなさい」。そして料理学校へ行くよう勧めてくれました。日本に残るつもりだった私に、彼女はパリへ行くよう強く勧めました。以前行ったことがあり、言葉も話せたので現実的でした。静代さんは、自分と同じ道をたどってほしかったのです。迷いはありましたが、結果的に私はその助言に従い、フランスへ渡りました。そして、その選択を後悔したことは一度もありません。物事はとても良い形で進み、人生の新たな章が開かれ、学び、前進し、新たな挑戦に向き合う力を与えてくれました。

アメリカに戻りニューヨークへ来た当初、私は自分の物語はフランスと日本での経験によって定義されるものだと思っていました。ここで、自分が見て学んできたものに強く結びついた料理スタイルを確立しようと考えていたのです。アメリカでは多くの人がその国々に関心を持っており、それがキャリアになると思いました。今もなおそれらに強い興味はありますが、ここに来て気づいたのは、「アメリカ人としての視点」で自分の声を見つけ、自分の物語を語ることの重要性でした。フランスや日本での暮らしをどれほど熱心に学んでも、その本質を本当に理解していると言えるのか、という問いがあったからです。

私は、アメリカ人としての視点から料理を通じて自分の声を見つけたいと強く思いました。しかし、アメリカ料理とは何なのでしょうか。アメリカの食とは何なのか。実は今、世界中が同じ問いを自らに投げかけています。「アメリカ料理とは何か」「どこへ向かっているのか」「何がそれを定義し、なぜ面白いのか」「本当に人々は興味を持っているのか」。私の答えは、はっきりとしたイエスです。グラマシー・タバーンに来られたことを、私は本当に幸運だと感じています。ここはアメリカ料理を語るための最高の舞台であり、同時に、まさにアメリカを象徴するレストランです。私はこの注目度の高い舞台で、自分のスタイルを進化させ、物語を語る自由を与えられてきました。

グラマシー・タバーンの物語に新たな章を加える

愛されてきたレストランに足を踏み入れることは、私がこれまで経験した中で、最も簡単であり、同時に最も難しいことでした。既存のチーム、既存のレストランに加わるとき、自分の足跡を残すことは簡単ではありません。このレストランは、私が来る前からすでにニューヨークで最も愛される店のひとつでした。最終的な決断を下す前に、私は自分に問いかけました。「この物語に、何かを加えることはできるだろうか」。それは私が採用するすべての人に投げかける問いでもあります。「この物語に加える勇気はありますか」と。職種や経験に関係なく、ここに来るすべての人が物語に貢献できるし、そうあるべきなのです。それこそが、この場所をダイナミックにしている理由です。私たちは、少数の個人の集合体ではなく、チームなのです。

もうひとつ、私が必ず聞く質問があります。「あなたは、自分が引き継いだ持ち場を、来たときよりも良い状態で去れると思いますか」。それは単に「片づけができるか」という意味ではありません。毎日、自分自身や周囲の人に対して重要な問いを投げかける、知的な姿勢を持って仕事に向き合えるかどうかということです。チーム全体に高い基準を求め、それを友好的で対立的でない形で実行できるか。それは簡単なことではありません。考えてみると、私が新しい人に投げかけるこれら二つの質問は、技術的なスキルとはまったく関係がありません。すべては、仕事に対する感情的な向き合い方に関わるものなのです。

私は自分にこう問いかけます。「自分の中で、最も長く残っている記憶は何だろうか。それはどこから来て、なぜ今も残っているのか」。人間の記憶はとても選択的です。どれほど熱心に学んだ知識でも、試験や規則として覚えた情報は、時間とともに薄れていきます。しかし、永遠に残るものは感情の記憶に根ざしています。料理もまた、特定の季節と強く結びついています。私は日本で暮らした経験を通して、その季節性を強く意識するようになりました。それが私たちの指針であり、食卓に並ぶものは季節の移ろいによって決まります。日本料理は、詩や芸術、人生観や哲学にまで通じる、季節とのつながりを私たちに教えてくれました。その感覚はとても重要で、私はそれを学び、グラマシー・タバーンの一部にしたかったのです。

このレストランに加わった後、妻の家族の一人がこう言いました。「素晴らしいわね、マイク。こんなにも愛されている有名なレストランのシェフになるなんて。グラマシー・タバーンが大好き」。彼女は自分の体験を思い浮かべていました。とても男性的で、重厚で、温かく、活気に満ちたレストラン。薪の煙の香りが漂う空間です。彼女はこう続けました。「グラマシー・タバーンは、永遠に11月みたいな場所」。その瞬間、私は「自分はこの店に何を加えられるのか」という問いの答えを見つけました。私は、この店を“四季すべてのレストラン”にしたかったのです。季節の食材を市場から仕入れることはもちろん大切ですが、それだけではありません。庭や畑、海、グリーンマーケットとレストランがどうつながるのか、その物語をさらに深めたかったのです。それはこの街にとって最も貴重な資源であり、この土地で育つ素晴らしいものすべての入口なのです。そして、それが私たちの文化の一部であることを伝えたかったのです。

良い方向へ天秤を傾ける

私たちの会社は約2年前、チップ制度を廃止するという決断をしました。ニューヨーク州、そして全米の法律では、チップをレストラン内で公平に分配することができず、報酬の不平等が生まれていたからです。チップの起源をたどると、それは奴隷制度に根ざした、深く偏った仕組みの名残でもあります。現代のアメリカでも、チップは個人の満足や個別報酬と結びつき、時にスティグマや、生活のために耐えなければならない露骨な虐待を生みます。その多くを女性やマイノリティが背負っています。これが大きな構図です。

ニューヨークのような大都市では、多くの高級レストランが、大人数の人件費を賄うためにチップ制度に依存しています。価格が上がればサービススタッフの収入は増えますが、時給制のキッチンスタッフの収入はほとんど変わりません。私たちは、この仕組みに終止符を打ちました。

私たちのレストランはチームワークがすべてです。チップなしの制度は、専門職としての文化を育み、アメリカのレストラン業界に蔓延する不安定さを取り除きます。日本やフランスで当たり前とされるような、誇りと献身を共有できる環境をつくります。スタッフは生活のために奔走するのではなく、学び、旅し、成長することができます。すべてのポジションに公平性が生まれ、子どもを持つ母親も、かつては男性ベテランが独占していたランチシフトに同じ給与で入れるようになりました。学歴や背景を問わず、誰もがキャリアの道筋を見通せる透明性が生まれたのです。

キッチンからコミュニティへ

アメリカ文化は、私たちの味覚を均質化し、季節感を平坦にしてきました。それは時に便利でもあります。世界中の料理を、いつでもどこでも食べられる都市に住めるのは素晴らしいことです。しかし私は、その土地で育つものを通してアメリカの物語を語るほうが、ずっと面白いと思います。愛されていたものが消え、また翌年に蘇る、その切なさと喜び。その感情を次世代に残すために、私たちは何ができるのか。それは環境問題とも深く結びつき、料理人を教育者として位置づけます。私たちはコミュニティに貢献できる存在であり、この街、この国で生き働くことの魅力を世界に伝えることができるのです。

グラマシー・タバーンを訪れたことは、マイケルの洞察や、レストランの背景にある思想を知る素晴らしい機会でした。専属のフローリストがいて、来店客を迎えるために生花を飾っていると知ったときは驚きました。マイケルはレストランの中を案内してくれ、キッチンの動きやスタッフのエネルギーも感じることができました。ニューヨークに来たら、ぜひグラマシー・タバーンを訪れてください。文句なしにおすすめです。

2017年11月、ニューヨークの Gramercy Tavern にて取材。 編集:My Philosophy 編集部 写真:Sebastian Taguchi