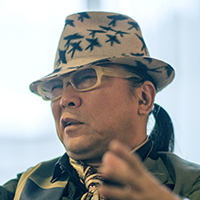

Masaaki Miyazawa, a distinguished figure renowned for his versatile photography in photo books, magazines, advertising, and fashion, has recently expanded his artistic horizon by capturing the serene beauty of Ise Jingu and Japan's pristine landscapes through his lens in both photography and film. In this interview, Mr. Miyazawa shares his profound experiences photographing Ise Jingu and expresses his hopes and insights for the younger generation.

Profile

Vol.90 Masaaki Miyazawa

Photographer | Film Director | Visual Director

Born in Tokyo in 1960, Masaaki Miyazawa graduated from the Department of Photography of Nihon University College of Art. In 1985, he was awarded the first Newcomer's Prize by the International Center of Photography in New York for his work "Yume Jūya (Ten Nights of Dreams)," which utilized infrared film. Beginning in 2005, he was granted official permission to photograph the 62nd Ise Jingu Shikinen Sengu (a periodic reconstruction event for the Ise Jingu shrines), marking a significant milestone in his career. In 2015, Miyazawa made his directorial debut with the documentary film "Umi Yama Aida; In Between Mountains and Oceans," which won the "Best Foreign Language Documentary" and "Best Producer" awards at the Madrid International Film Festival. His portfolio includes over 150 photo books of actors, actresses, and artists available on Amazon, and his work spans various mediums, including advertisements, music videos, and commercials, showcasing his broad and diverse talents in the field.

Turning Passion into Profession

Entering the world through photo art, I received an award in New York and upon returning home, I was flooded with work related to fashion and advertising. It might be the same in every industry, but in Japan’s photography scene, there are those who prefer clear boundaries, saying things like, “’Why is someone who did art now doing fashion?”’ or “’Now a fashion person has come to advertising.”’ I had no intention of disrupting the industry; I was just young and couldn’t say no to the jobs offered to me. I simply loved photography and film, and wanted to pour my energy into themes I wanted to capture.

A photographer can’t survive on artwork alone. For me, photography is not just a job but a lifelong work as a photographer, with another track running parallel as my career. Because I make a living doing what I love, I enjoy the competition of trying to reach the top in every field, despite crossing industry boundaries and sometimes facing criticism.

Everyone struggles to make decisions. The fear of failure can prevent you from stepping forward. But it’s better to take on challenges than do nothing. I’ve always acted quickly on inspiration without overthinking. I’ve been deceived many times, but as long as I don’t repeat the same mistakes, it’s all a learning experience. In your 20s and 30s, it’s hard to make decisions alone. That’s when it’s good to consult a mentor or a trusted elder. Rethink their advice, and if you feel it’s better to act than not, then decide and move forward. I often consulted with author Shizuka Ijuin, who I respect like an older brother.

Entering the world through photo art, I received an award in New York and upon returning home, I was flooded with work related to fashion and advertising. It might be the same in every industry, but in Japan’s photography scene, there are those who prefer clear boundaries, saying things like, “’Why is someone who did art now doing fashion?”’ or “’Now a fashion person has come to advertising.”’ I had no intention of disrupting the industry; I was just young and couldn’t say no to the jobs offered to me. I simply loved photography and film, and wanted to pour my energy into themes I wanted to capture.

A photographer can’t survive on artwork alone. For me, photography is not just a job but a lifelong work as a photographer, with another track running parallel as my career. Because I make a living doing what I love, I enjoy the competition of trying to reach the top in every field, despite crossing industry boundaries and sometimes facing criticism.

Everyone struggles to make decisions. The fear of failure can prevent you from stepping forward. But it’s better to take on challenges than do nothing. I’ve always acted quickly on inspiration without overthinking. I’ve been deceived many times, but as long as I don’t repeat the same mistakes, it’s all a learning experience. In your 20s and 30s, it’s hard to make decisions alone. That’s when it’s good to consult a mentor or a trusted elder. Rethink their advice, and if you feel it’s better to act than not, then decide and move forward. I often consulted with author Shizuka Ijuin, who I respect like an older brother.

The Place for Artwork

About 13 years ago, I started a company called Masterworks to lend out my work. I wanted my work to stand on its own. When my work stands on its own, it means I do too. Posters in stations last a few weeks, magazine covers one week, newspaper ads just a day, but my work are displayed permanently in hotels, offices, golf courses, public facilities, restaurants, and more.

Selling my work or having it displayed is crucial for me. Artists, including photographers, might as well be dead if their work isn’t shown. I believe the essence of my photographic life is to have my work appreciated like background music, subconsciously impacting viewers. While I seek work opportunities in posters and magazines, I think it’s important to find places that will honor my work as art.

At Masterworks, we rent out pieces relatively inexpensively, which has increased corporate requests and recognition. I enjoy meeting various people through work, but ultimately, I’m happiest focusing solely on creating art. In my retirement, I want to take photos I love. If there’s a system where I can support myself and my family, travel where I want, take photos, and exhibit them wherever I choose, I believe it would not only benefit me but the photography world as well. [Visit Masaaki Miyazawa’s Online Photography Store]

About 13 years ago, I started a company called Masterworks to lend out my work. I wanted my work to stand on its own. When my work stands on its own, it means I do too. Posters in stations last a few weeks, magazine covers one week, newspaper ads just a day, but my work are displayed permanently in hotels, offices, golf courses, public facilities, restaurants, and more.

Selling my work or having it displayed is crucial for me. Artists, including photographers, might as well be dead if their work isn’t shown. I believe the essence of my photographic life is to have my work appreciated like background music, subconsciously impacting viewers. While I seek work opportunities in posters and magazines, I think it’s important to find places that will honor my work as art.

At Masterworks, we rent out pieces relatively inexpensively, which has increased corporate requests and recognition. I enjoy meeting various people through work, but ultimately, I’m happiest focusing solely on creating art. In my retirement, I want to take photos I love. If there’s a system where I can support myself and my family, travel where I want, take photos, and exhibit them wherever I choose, I believe it would not only benefit me but the photography world as well. [Visit Masaaki Miyazawa’s Online Photography Store]

Let’s Go on a Journey

Work used to be a painful necessity for survival. Nowadays, we often hear that we should make a career out of what we love, but many young people struggle to find their passion and don’t know what to do. When I was younger, I was taught, “If thinking doesn’t solve it, try doing it.” Wondering what would happen if you didn’t eat, or trying to run a full marathon, might be worth the effort at least once. I’m not in favor of conscription like in South Korea, but I believe some degree of mental and physical training can be beneficial for personal development, rather than living life aimlessly. It’s abstract to simply tell someone to be passionate about something, so taking a book that you can use as a base for your activities and going on a journey might be a good idea. In Japan, you can travel economically by bus or train. Even a one or two-night trip can be sufficient if it’s a journey to find yourself. It’s important to step outside your current environment and explore.

As a student, I didn’t find beauty in certain views, and I thought power lines were a nuisance. But now, I’ve come to see them as part of the landscape. Ideally, it’s better that they wouldn’t exist, but they are part of the reality of our living environment, something that didn’t exist in the Edo period. Perhaps because I’m a photographer, I wonder why Hokusai painted Fuji Mountain the way he did, and I think about how to capture the “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” in the modern era. Even if you’re not a photographer, comparing and capturing the traditions and culture of Japan, past and present, can make an ordinary scene look fascinating and make for an interesting journey.

Work used to be a painful necessity for survival. Nowadays, we often hear that we should make a career out of what we love, but many young people struggle to find their passion and don’t know what to do. When I was younger, I was taught, “If thinking doesn’t solve it, try doing it.” Wondering what would happen if you didn’t eat, or trying to run a full marathon, might be worth the effort at least once. I’m not in favor of conscription like in South Korea, but I believe some degree of mental and physical training can be beneficial for personal development, rather than living life aimlessly. It’s abstract to simply tell someone to be passionate about something, so taking a book that you can use as a base for your activities and going on a journey might be a good idea. In Japan, you can travel economically by bus or train. Even a one or two-night trip can be sufficient if it’s a journey to find yourself. It’s important to step outside your current environment and explore.

As a student, I didn’t find beauty in certain views, and I thought power lines were a nuisance. But now, I’ve come to see them as part of the landscape. Ideally, it’s better that they wouldn’t exist, but they are part of the reality of our living environment, something that didn’t exist in the Edo period. Perhaps because I’m a photographer, I wonder why Hokusai painted Fuji Mountain the way he did, and I think about how to capture the “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” in the modern era. Even if you’re not a photographer, comparing and capturing the traditions and culture of Japan, past and present, can make an ordinary scene look fascinating and make for an interesting journey.

Always Striving for Something Better

The 12 years I spent photographing Ise Shrine were the peak of my career as a photographer, from age 43 to 55. When young, you might have the energy, but your skills are still developing. That period was when my skills, experience, and sensibilities as a photographer were at their best. What stands out in my memory is sneaking in like a cat to photograph ceremonies in the dead of night where no one else was allowed to shoot, the tension of accessing restricted areas during the Kannamesai festival, and the thrill of capturing those moments, all the while making various adjustments to silence the shutter sound. Each of those moments has stayed with me.

About a year after I started shooting, I felt as though I had captured everything. But when I laid out the photos, I realized I had only captured the surface. I was so engrossed in shooting that I missed capturing the mythical world I had envisioned.

I’ve always been drawn to abstract themes, and my work “Yume Jūya (Ten Nights of Dreams),” which won an award in New York, aimed to capture an unreal world, creating a wonderland that only I could see, based on dreams and mental landscapes. The theme of mythology for the Ise Shrine project was an extension of this, aiming to capture a unique, otherworldly perspective that only I could achieve.

I realized that when looking through the viewfinder, I wasn’t imprinting anything in my mind or heart. So, for two to three months, I visited the shrine early in the morning without my camera, forcing myself to wait and truly see and imprint the scenes in my mind. One of the photos I took later became the cover of the official photo book of Ise Shrine at the time. A ray of light piercing through from the sanctuary of Amaterasu Omikami to the path of the Inner Shrine felt like the beginning of a myth. From then on, I was able to capture myths reborn in the modern age.

What I capture is not “records” but “memories.” When I managed to take the photo for the cover, I felt I finally encountered it. By visiting the deserted early mornings without carrying a camera for about three months, I came across this scenery. Had I not done that, I would have missed this atmosphere. It is because the technology has matured that I learned to go a step further.

I must always update myself, beyond the photos I have taken today, tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow. In any job, even if the subjects are the same, your level will steadily increase if you capture something better than before. It’s not about doing the same thing as before or something slightly different; you must create something even better. I am always thinking about how I can make the best update for the next job that comes along.

The 12 years I spent photographing Ise Shrine were the peak of my career as a photographer, from age 43 to 55. When young, you might have the energy, but your skills are still developing. That period was when my skills, experience, and sensibilities as a photographer were at their best. What stands out in my memory is sneaking in like a cat to photograph ceremonies in the dead of night where no one else was allowed to shoot, the tension of accessing restricted areas during the Kannamesai festival, and the thrill of capturing those moments, all the while making various adjustments to silence the shutter sound. Each of those moments has stayed with me.

About a year after I started shooting, I felt as though I had captured everything. But when I laid out the photos, I realized I had only captured the surface. I was so engrossed in shooting that I missed capturing the mythical world I had envisioned.

I’ve always been drawn to abstract themes, and my work “Yume Jūya (Ten Nights of Dreams),” which won an award in New York, aimed to capture an unreal world, creating a wonderland that only I could see, based on dreams and mental landscapes. The theme of mythology for the Ise Shrine project was an extension of this, aiming to capture a unique, otherworldly perspective that only I could achieve.

I realized that when looking through the viewfinder, I wasn’t imprinting anything in my mind or heart. So, for two to three months, I visited the shrine early in the morning without my camera, forcing myself to wait and truly see and imprint the scenes in my mind. One of the photos I took later became the cover of the official photo book of Ise Shrine at the time. A ray of light piercing through from the sanctuary of Amaterasu Omikami to the path of the Inner Shrine felt like the beginning of a myth. From then on, I was able to capture myths reborn in the modern age.

What I capture is not “records” but “memories.” When I managed to take the photo for the cover, I felt I finally encountered it. By visiting the deserted early mornings without carrying a camera for about three months, I came across this scenery. Had I not done that, I would have missed this atmosphere. It is because the technology has matured that I learned to go a step further.

I must always update myself, beyond the photos I have taken today, tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow. In any job, even if the subjects are the same, your level will steadily increase if you capture something better than before. It’s not about doing the same thing as before or something slightly different; you must create something even better. I am always thinking about how I can make the best update for the next job that comes along.

Photographer | Film Director | Visual Director Masaaki Miyazawa

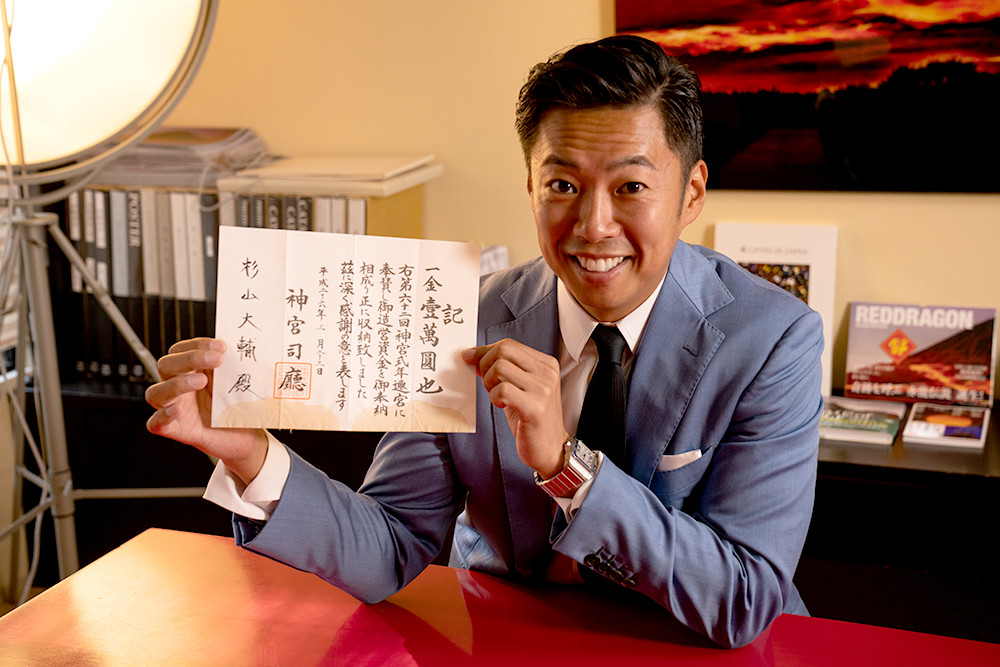

In 2014, portrait photographer Yu Kaida, who appeared in the 27th volume of “My Philosophy”, said to me, “Daichan, this year is the Shikinen Sengu at Ise Shrine, which happens once every 20 years, so let’s go together. It’s a place all business leaders should visit,” and I went with my family. The gifts we received for our dedication were a fan and a photo book taken by Masaaki Miyazawa. I felt a connection and realized that the meaning behind actions follows afterwards. On my 30th birthday, when I had drinks with my father, he told me, “Go abroad and visit various places to see them with your own eyes.” For instance, if you are asked to create a building with the ambiance of New York’s Grand Central, you can’t propose anything if you haven’t seen it yourself. Seeing things for yourself is important, and continuing to take action in my 30s allowed me to meet the amazing photographer, Mr. Miyazawa. Hearing about his dedication and focus on photographing Ise Shrine for 12 years, I realized that you need to dedicate at least a decade to truly see and understand something. I intuitively felt that I wanted to work with him, so I determined to create opportunities to work together. Once you decide on something, everything comes together in the right place.

August 2018 at Masaaki Miyazawa Photography Office Inc. Writer: Naomi Kusuda Photographer: Tetsugoro Takamura