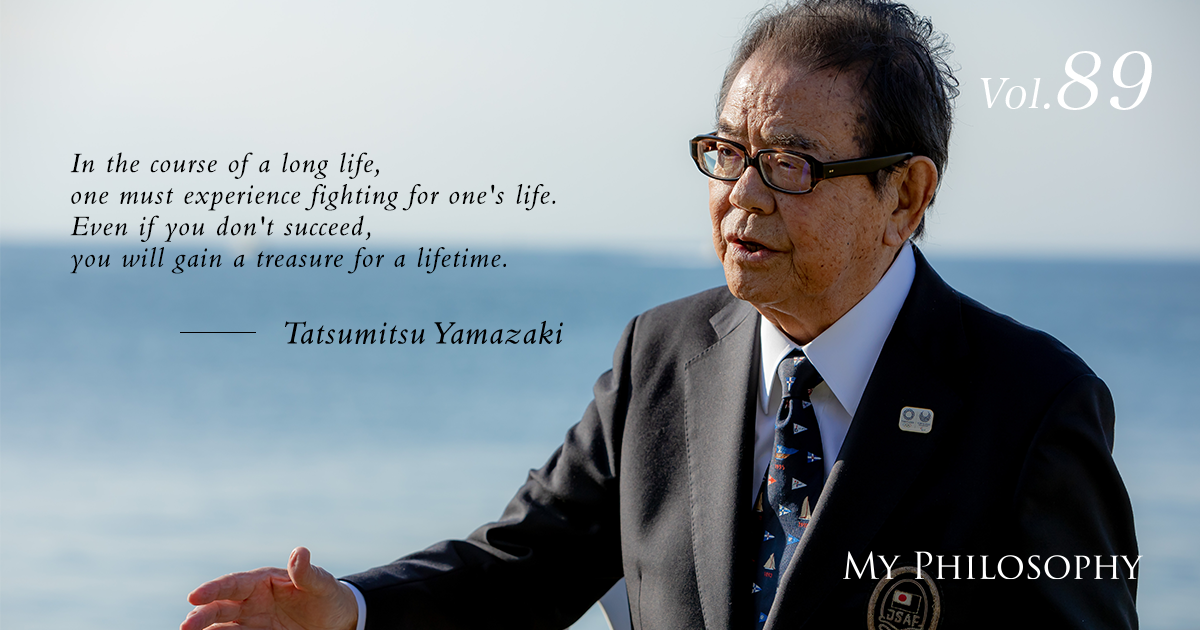

Mr. Tatsumitsu Yamazaki, who organized the "Nippon Challenge for the America's Cup" and competed three times in the America's Cup, the world's premier yacht race that has been held since 1851. We had the opportunity to speak with him about his feelings towards the sea and his spirit of challenge.

Profile

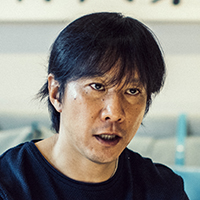

Vol.89 Tatsumitsu Yamazaki

Honorary Chairman of the Japan Sailing Federation | Former Chairman of S&B Foods Inc.

Born in Tokyo in 1934, Mr. Tatsumitsu Yamazaki graduated from Waseda University, where he was a member of the yacht club. After graduating, he joined S&B Foods Inc. He served as the President from 1983 to 1989 and as Chairman from 1989 to 2003. Additionally, as the owner of the yacht "Sunbird," he was active in offshore sailing races. From 1974 to 1994, he was a director of the Nippon Ocean Racing Club. He organized the Nippon Challenge and competed in the world's oldest yacht race, the America's Cup, in 1992, 1995, and 2000, achieving the top four positions in all three challenges. From 2001 to 2011, he served as the chairman of the Japan Sailing Federation and is now its honorary chairman. He is the author of "The Day the Sea Burned (Umi ga Moeta Hi)" (Kazi Co., Ltd.).

Mr. Tatsumitsu Yamazaki passed away on December 6, 2020, at the age of 86. Through this article, we are grateful for the opportunity to convey Mr. Yamazaki’s spirit of challenge, who loved the sea and competed with the world. I sincerely pray for his eternal peace. DK Sugiyama, Editor-in-Chief, “My Philosophy”

The Emergence of a Challenge Spirit

Originally, the idea of challenging for the America’s Cup was like a dream within a dream within another dream in our world of sailors, let alone thinking that I would be the one to undertake it. Life is truly unpredictable. In 1985, when I participated in the Transpacific Yacht Race from Los Angeles to Hawaii, Dennis Conner, who was then known as Mr. America’s Cup and an American hero, was practicing nearby. I decided to sail alongside him from a distance. His famous yacht, “Stars & Stripes,” was a 12-meter class (*1), while my “Super Sunbird” was a 40-foot cruiser. Although my boat was not a match in terms of size, strength, or power, surprisingly, when it came to upwind (*2) conditions, we were able to keep pace with each other. At that moment, I thought to myself that we might stand a chance in the America’s Cup.

About a year before this, some people started saying that it was about time for Japan to challenge the America’s Cup. These were prominent figures in Japan’s offshore yachting community: the late Kaoru Ohgimi (former Vice Chairman of the Nippon Ocean Racing Club), Takao Ninomiya (a maritime historical novelist), and Taro Kimura (a newscaster). They would come to my office almost every week, urging me to take on the challenge of the America’s Cup. At that time, I wasn’t particularly enthusiastic. The America’s Cup seemed like nothing more than a dream; I had no idea where to start, whether it was building a yacht from scratch, training a crew, or forming a team.

However, the experience in Hawaii made me think that, even though I didn’t believe we could win, perhaps it was worth taking on the challenge.

My Feelings Towards the Sea

The sea is, for me, a place of emotional refuge. Just looking at the sea brings me peace, and it feels as if all problems are being resolved. My first encounter with a yacht happened during my middle school years when I visited a beach house in Tateyama, Chiba, owned by my father, during the summer holidays. There, at the pier, yachts were available for free, and I set out to sea without really knowing how to handle one. I wondered, “If I keep going straight, where will I end up? Could I reach Hawaii?” The thought scared me, and I turned back, but I still remember the excitement I felt.

When we decided to challenge the America’s Cup in 1992, Japan’s economy was in the aftermath of the bubble era collapse, and there was an atmosphere of questioning, “Is it okay for Japan to stay this way?” The challenge required a huge amount of money. I went around asking for sponsorship through various connections. Normally, it would be hard to agree to sponsor an event with such low recognition in Japan when considering the cost-effectiveness. However, many companies said, “Mr. Yamazaki, you should do it.” They saw it not just as sponsoring an event but as a fight to preserve and maintain Japan’s maritime culture. There was also a strong sentiment that the Japanese should learn a new way of relating to the sea.

Despite being surrounded by the sea and benefiting from it since ancient times, it’s unfortunate that the seas of Japan are polluted, with turtles dying from straws stuck in their eyes and whales suffering from ingesting plastic bags. The challenge for the America’s Cup was not merely about participating in a yacht race; it was also a demonstration of inheriting and continuing Japan’s maritime culture and traditions. It was a challenge that signified being a nation that lives with and faces the sea.

Integrity and Dignity

To advance a large project, three things are necessary: people, materials, and money, among which people are undoubtedly the most important. In my 50s, I was fortunate to have many sponsors who provided not just financial support but also wisdom and mental support. One of them, Mr. Sumao Tokumasu, who was the president of Sumitomo Marine & Fire Insurance Company Ltd., at the time, taught me the phrase “Sei Sei Do Do (正正堂堂).” He explained, “It’s different from the high school baseball tournament’s concept of entering the field with dignity. It refers to a principle from The Art of War by Sun Tzu: ‘Do not engage in battle in a straightforward manner, and do not attack an enemy who has prepared a grand and solid formation.’ It means victory belongs to those who are thoroughly prepared.”

In essence, “正正堂堂” refers to an army that is thoroughly prepared. The Nippon Challenge was to build the best yacht, train the strongest crew, and present ourselves as a formidable force in the eyes of our rivals.

In 1995, during our second challenge, we had to perform a major surgery on our challenge yacht, JPN-30 (*3), by dividing it into three parts: the front, center, and rear, in San Diego due to unsatisfactory tuning. Nonetheless, we ended up losing in the semifinals and incurred the most debt. I believe that challenge lacked the spirit of “正正堂堂” because we were not sufficiently prepared.

For Honor Alone

It was a great pleasure to be able to take on this challenge with trusted companions. We challenged in 1992, 1995, and 2000, and including the preparation periods for each, we maintained a challenger’s spirit continuously for about 15 years. The America’s Cup is the ultimate yacht race, and the Nippon Challenge was a grand project.

Normally, you would get tired of it along the way. But not just me, the crew and staff, everyone was motivated by the desire to win the America’s Cup. I believe that we all acted “for honor alone”.

The Spirit of Challenge Continues

For 17 years after my third challenge, until 2017, no Japanese challenged the America’s Cup (*5). Had I not taken up the challenge then, Japan might still not have participated. Challenging is not easy; it’s truly a fight for your life. But if it’s not that, can it even be called a challenge?

**About the America’s Cup**

The America’s Cup began in 1851, as a commemorative event for the first ever World Expo held in London. The yacht “America” won a race against the fast ships of maritime nation Britain, bringing home a trophy worth 100 guineas. Since then, for nearly 140 years, yachtsmen from around the world have competed for the cup, staking their countries’ prestige in what has become the world’s premier yacht race.

Annotations

- *1)The 12-Meter Class: A rule for yachts used from the 1958 to the 1987 competitions. The actual waterline length is about 23 meters, not 12 meters.

- *2)Upwind: Yachting involves alternating between sailing upwind and downwind. The speed of upwind sailing is said to be determined by the yacht’s design performance.

- *3) JPN-30: The sail number assigned to boats in the International America’s Cup Class, used from the 1992 to the 2007 competitions. The alphabet denotes nationality, and the number represents a sequential identifier.

- *4) “For Honor Alone”: Challenging for the America’s Cup requires vast funds, but winning only secures a trophy, with no prize money or awards given. However, the winning nation gains the right to host the next event.

- *5)In the 2017 competition, “SoftBank Team Japan” represented Japan’s first challenge in 17 years. Like the Nippon Challenge, they were defeated in the semifinals and finished fourth.

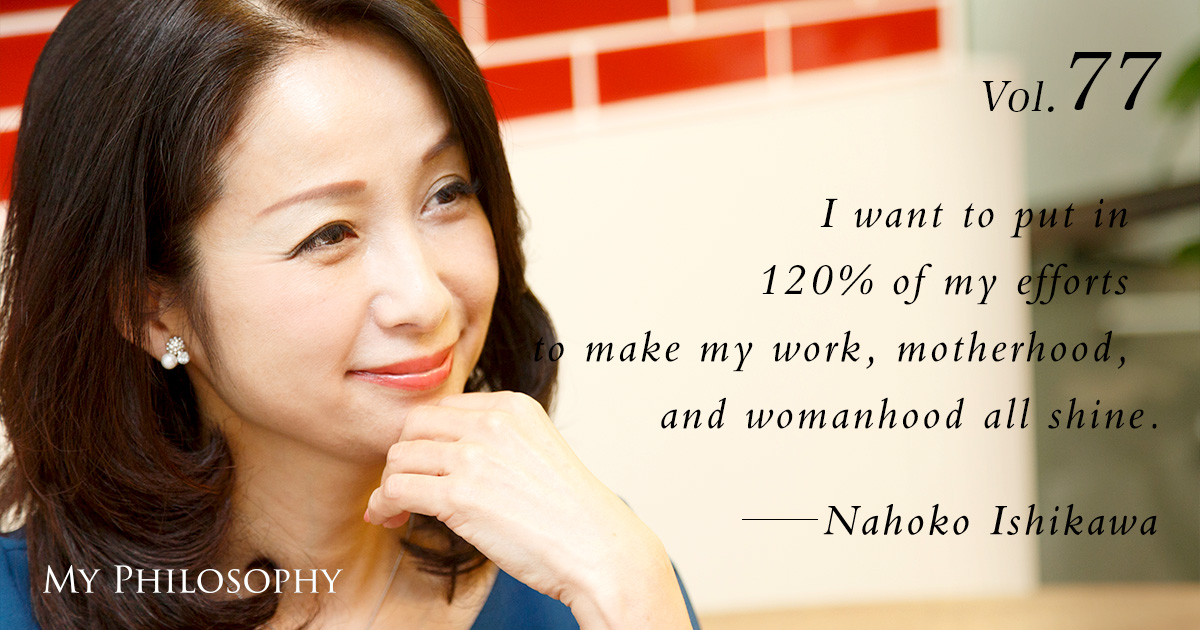

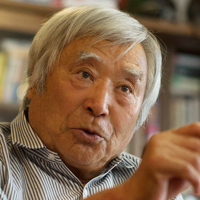

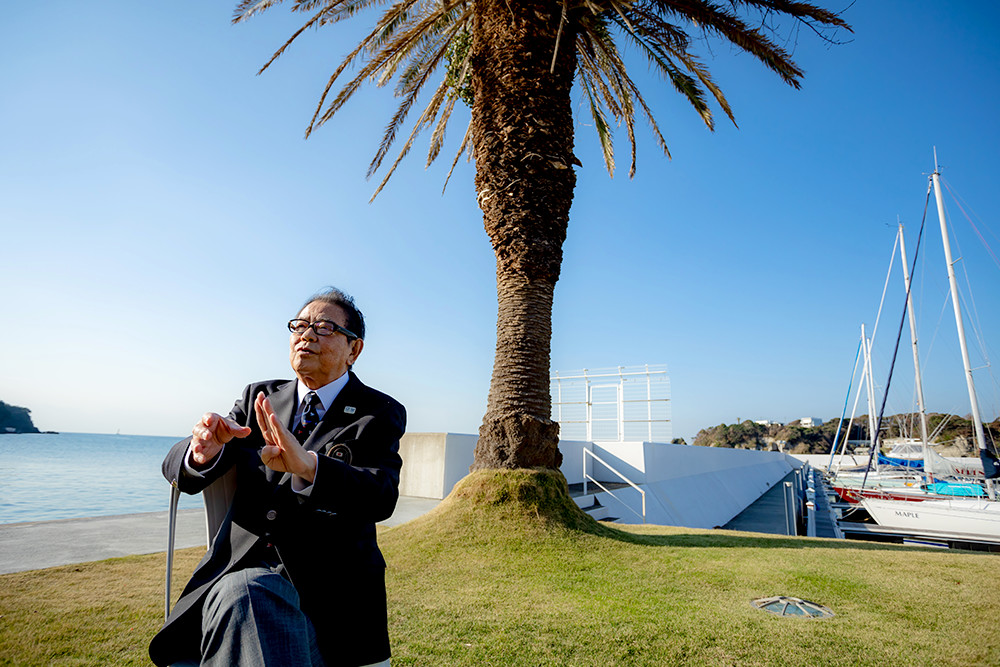

I served as the second commodore of the Seabornia Yacht Club. Seabornia always brings me wonderful encounters. That day, under the clear blue sky, I had an incredibly enjoyable time talking about the sea with a young man who loves the sea and is not afraid to challenge it, DK Sugiyama. This article will remain as my monument.

Tatsumitsu Yamazaki, Honorary Chairman of the Japan Sailing Federation

Like the song that goes, “The sea is vast, so immense,” I love the sea that connects us to the world. After a senior advised me, “Daisuke, boats are wonderful!” I became even fonder of the sea upon obtaining my Class 1 Small Boat Pilot’s License. In 2016, I went to watch the Louis Vuitton America’s Cup World Series in Fukuoka. Tatsumitsu Yamazaki is the first Japanese to challenge the America’s Cup, a figure well-known among Japanese yachting enthusiasts.

Through his books and interviews, I sensed that it would have been impossible to take on the world’s premier yacht race without an immense spirit of challenge. There are no breaks in yacht racing; you can’t just ask for a timeout. The record of challenging three times and making it to the semifinals each time is simply remarkable.

Knowing that he continues to maintain a challenging attitude, I’m reminded that age is irrelevant when it comes to taking on new challenges. This article was posted on Mr. Yamazaki’s birthday, November 30th. Happy 84th birthday, Mr. Yamazaki!

October 2018, Riviera Seabornia Marina, Miura Peninsula Writer: Naomi Kusuda, Photography: Akane Inagaki