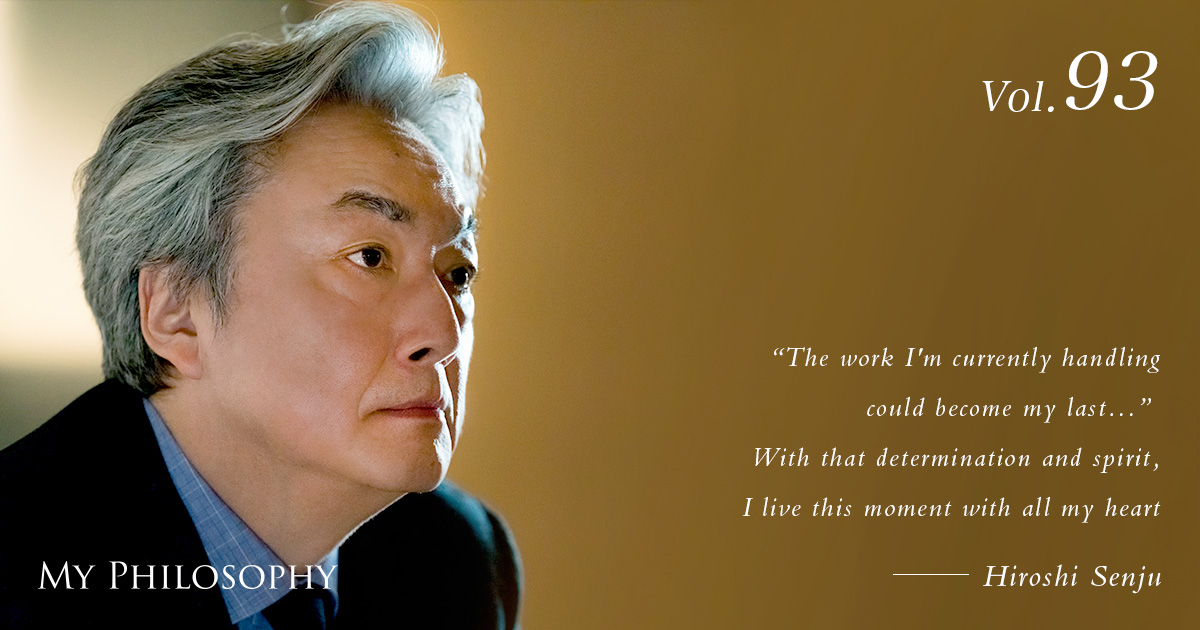

This year (2019) marks the 40th anniversary of the painting career of Hiroshi Senju, a Japanese painter. He has produced over 10,000 pieces to date. Yet, he continues to discipline himself with the belief that he has not yet created his masterpiece, never fully satisfied with the past, and actively continues his creative endeavors. The passion for painting has remained unchanged for 40 years. Where does the source of this passion lie?

Profile

Vol.93 Hiroshi Senju

Japanese Painter | Professor at the Graduate School of Kyoto University of the Arts and Design

Born in Tokyo in 1958. Graduated from the Tokyo University of the Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Painting. Completed the doctoral program at the same university but left before obtaining a degree. He has exhibited twice at the Venice Biennale (in 1995, he was the first person of Asian artist to receive an Honorable Mention for a painting), as well as in the Gwangju Biennale, Chengdu Biennale, and Milan Salone.

In 2016, he was selected for the "Heisei Era National Treasures of Japan" at Yakushiji Temple and received the "Minister of Foreign Affairs Award" for the fiscal year 2016. In 2017, he was awarded the 4th Isamu Noguchi Award, and in 2018, he received the " Eagle on the World Award by the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry of New York (JCCI)."

His works are highly regarded internationally, with collections and exhibitions at major world art museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Confronting the “Inadequate Self”

For 40 years, I have faced my paintings with fervor, regardless of the period. Yet, looking back at my past works now, I find myself thinking they are all quite amateurish. This feeling is probably not unique to me; I believe most artists feel this way. For instance, the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, when asked which of his works was his masterpiece, famously replied, “The next one.”

I understand his sentiment. Although I’m conscious of having dedicated myself fully at each moment, I do not think about making additions later. Yet, with every piece I’ve created, there’s a lingering regret that perhaps it was not enough.

On the other hand, I find it crucial to leave behind works that I consider inadequate. The reason is that the regret of having left behind something imperfect serves as a catalyst for the next work. If I were to look back at my past works and feel completely satisfied, thinking I did well, then no greater work would come from me thereafter. I would no longer think about surpassing my current self. Despite striving for perfection every time, upon completing a piece, I often find myself thinking, “What is this?”

Being crushed by my inadequacies, enduring that, creating a new piece, and then being faced again with my inadequacies, enduring further… This cycle has been repeated over the last 40 years. “This is inadequate, that is inadequate, so what should I do?” Thinking about this and connecting it to the next effort is, I believe, what life is about.

What Sustains Perseverance is “Physical Strength”

The reason why those referred to as “masters” are considered great is because of their resilience; despite being confronted with their inadequacies, they have the perseverance to bounce back the next day and confront their work. They have rebounded with a never-give-up attitude for 60, 70 years, far more than myself. It is this admirable resilience that makes them worthy of respect as human beings. So, what do you think underpins this perseverance? It is physical strength.

When I am beaten down by my inadequacies, I go home, immediately cover myself with a futon, and fall asleep. Sleeping restores my physical strength and brings back the energy to face my work again, thinking, “One more time, just one more time.” For me, there is only “painting.” I cannot do anything else but “paint.” There are many people who are better than me at studying, languages, cooking. There are those who are better writers, smarter, more excellent, more stylish. Without painting, I might not have been able to find my social presence. Painting was the only path that allowed me to live. Therefore, I have no choice but to commit myself fully. I have painted “10,000” paintings so far, but I have never considered a single one of them perfect. I am constantly downtrodden. Yet, the reason I can continue painting is because “I love painting.”

If You Want to Create Pure Works, Be a Pure Person

If you don’t understand what a painting is expressing when you see it, I think it’s a good idea to meet the person who painted it. A painting reflects everything about its creator. A person’s character is revealed in their art. No matter how beautiful the colors used, the creators of paintings that seem muddled can usually be understood upon meeting them. “Ah, so that person painted this.” What is necessary to paint a good picture is the formation of one’s character. Becoming a good person. Becoming a pure person. There is no other way to paint well.

When I was younger, there was a collector who said, “I don’t understand Mr. Senju’s paintings, but I believe in you.” I owe my present self to that person. Expression begins with being trusted by others. For an artist, above all else, what is necessary is humanity. The condition for becoming my disciple is not being able to paint well but having “honesty” and “politeness.” If one possesses honesty and politeness, they will eventually bear fruit, even if they cannot paint well now. In the past, when masters took on disciples, they first ordered them to clean the garden and look after their grandchildren. Why? They were seeing if the person could diligently do even menial tasks. In the creation of a work, the creative part is just a fraction; more than half is the repetition of simple tasks. When painting, you continue to apply the base coat tirelessly.

Much of the work involves only unpleasant, difficult things. Paint drops, cracks appear, compositions shift—a series of events that makes you want to give up. My brother and sister are musicians, and if it’s about music, they repeated the same practice over 1,000 times from a young age. Even if it’s unpleasant or boring, I believe that continuing to do it diligently is the most necessary quality for a creator.

Focusing on “Quantity” Rather Than “Quality”

Some say, “It’s the quality of the work that matters,” but those are the words of someone who has never painted. Everyone who creates something thinks, “Next time, I will make something of higher quality.” However, if it were possible to create something just by intending to, there would be no struggle. On the contrary, I believe that “quality is born from quantity.” A high-quality work is something that, by chance, gets mixed in while producing a large quantity.

Every single time, I finish painting with the thought, “This is the masterpiece.” Yet, when ten pieces are laid out, they naturally arrange themselves from first to tenth place, and most of the time, I think to myself that they are utterly inadequate. However, out of ten pieces, there might be one, out of twenty, one piece, and out of a hundred, one piece that makes me think, “This, I can accept.” Creators are thought to be creative, original, and unique, but that is a one-sided view. What is demanded is whether you can endure the painful process of stacking up simple tasks and quantity while believing in yourself.

Creators Need a Sense of Responsibility and Preparedness

Recently, we see many new art pieces created using digital technologies. Digital, like painting, reflects the humanity and sensitivity of the creator. If there’s a difference, it’s that digital can only convey visual and auditory information. It doesn’t convey smell, taste, temperature, texture, or space, making it an incomplete medium.

Another potentially dangerous aspect of digital is the ability to “erase” what we find unpleasant or obstructive. If there’s someone you dislike among the characters in a game, you can eliminate them with a single click. However, constantly interacting with digital characters can hinder the development of communication skills needed in the real world.

Dealing with people you dislike is a reality. True communication skills are developed by figuring out how to get along with difficult people, practicing this, and experiencing it. My concern is that becoming accustomed to “erasing” may lead people to choose easy solutions, like turning away if they don’t like something.

The audience for a work is selfish and diverse. Each person interprets the content sent into the world according to their values. Therefore, creators on the sending end need to imagine the impact their works will have on the world and create with a sense of responsibility and preparedness, hoping to establish genuine human communication. Whether it’s digital or painting, the humanity of those who send out works will be increasingly scrutinized in the future.

Only Those Who Are Prepared Can Seize Opportunities

For a painter, “to think” means to paint. When painters say they are “troubled,” it often means they are pretending to think while actually resting, or their minds are not functioning. Thus, even when I feel like I cannot paint at the moment, I still go to my studio and grasp my paintbrush. Instead of wasting time pondering with my arms crossed, I start painting. If there is sadness or difficulty in my heart, I paint over those feelings layer by layer. In this way, the work gains humanity. Therefore, this process is also an important act of “thinking” for the painter.

Painters are individuals whose minds start working and switch on only when they hold a paintbrush. To be ready to switch on at any time, I always make it a point to carry writing instruments and tools with me. Without constantly holding a paintbrush and being prepared, you cannot seize opportunities. The central element that composes a work is referred to as the “motif.” Even if a painter possesses talent or skill, without being blessed with a good motif, the allure of the artist as an expresser will not be fully showcased. That’s how crucial motifs are to painters. Finding a motif for a painting always happens suddenly—while in the studio, on a research trip, or training at the gym. It’s, so to speak, a “gift” that comes unexpectedly. When inspiration for a motif strikes, if you’re holding something unnecessary like sweets or alcohol, asking it to “wait a moment!” while you prepare will cause the inspiration to slip away. You must always be ready to paint to capture the opportunity.

Opportunities visit everyone equally. However, only those “who are prepared” can reach out and grab them. Novelists always carry a pen to write, and photographers always have their cameras ready. If you keep yourself prepared, I believe luck will be on your side.

Living “This Moment” to the Fullest

Once a month, I have the opportunity to fly, and each time, considering the possibility of a plane crash, I organize my belongings and tear up all the works I don’t want to be my last. I’ve made it clear to my assistants in the studio that if something happens to me, they are to destroy my works. If an assistant suggests, “Instead of tearing them, it’s a waste, so give them to me,” I would ask that assistant to leave. Even after a work has passed into someone else’s hands, if I feel unsatisfied with it, I will buy it back. Then, after thanking the piece, saying, “Thank you for everything up to now. You’ve helped me get this far. Now, please rest,” I tear it up. Japanese paintings, due to their materials, can last for a thousand years if not destroyed. It would be a pity for a “bad work” to be exposed to human eyes for a thousand years.

I have no regrets about dying at any moment because I live each day to the fullest, passionately and completely. I have no idea when “death” may come. It might be next year, or I might live another fifty years. It’s nonsensical to ponder things that are unimaginable. Therefore, I live with the awareness to “spend a life without regrets, even if I were to die the next moment.” If there’s someone I want to meet now, I go see them; if there’s something I want to eat now, I eat it. If there’s something I want to do, I don’t postpone it. The time to do what I want is “always now.” I believe that is what it means to be “alive.”

Looking back at the history of Japanese art, the majority of it is themed around “this moment.” For example, the concept of “Ichi-go ichi-e” in the tea ceremony represents the once-in-a-lifetime encounter, devoting sincerity to “this moment.” Ukiyo-e captures the fleeting moments of the “floating world” of reality, and from artists like Ogata Korin and Hasegawa Tohaku to the depictions of flowers, trees, and birds, their works overflow with awe for the rich, living nature of “now.” The focus of Japanese art has always been the “present world.” The same goes for Ikebana, facing the beauty of living now. Perhaps they were too captivated by the wonder of a momentary life to consider the afterlife. The work I’m currently handling could become my last… Being resolved to paint with that awareness is the only thing I can do regarding “death.” This very moment is brimming with life, and to enjoy that life 100% is more appealing than pondering over death.

Over the years, I have been interviewed by many people, but Daisuke Sugiyama struck me as particularly sharp. His responses were clear and to the point. In the past, some might have seen in him an image of the Bushido. I’ve read somewhere that Bushido is about being “clean and quick.” Cleanliness means not getting caught up in unnecessary details, not adorning oneself with trivialities. Being quick means not dawdling; move swiftly, but when it comes to the essentials, handle them with care to avoid needless loss of life on the battlefield. For example, the tea ceremony performed by samurais is incredibly fast, yet when handling the tools, they are as cautious as if shifting gears to first, which is a beautiful sight to behold. With this underlying aesthetic of Japanese Bushido, speaking fluent English and well-versed in manners, I am confident in the bright future of Daisuke Sugiyama, an international figure.

Hiroshi Senju, Japanese Painter

Having continued “My Philosophy” for 12 years and always acting upon it, I’ve encountered numerous individuals, witnessed miracles, and was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to interview Professor Hiroshi Senju. This interview was conducted before the opening at the Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi venue, surrounded by the wonderful works of art during the “40th Anniversary of Hiroshi Senju’s Art Career” exhibition.

The backdrop of Professor Senju’s works, particularly the waterfall piece, had a significant impact. Turning 40 this year, I am deeply influenced by Professor Senju’s dedication to painting throughout his life, the importance of persistence, and his earnest approach to living each day to the fullest. I look forward to having in-depth conversations at Professor Senju’s studio in New York next time.

February 2019, Nihombashi Mitsukoshi Main Store | Inside the Hiroshi Senju 40th Anniversary Exhibition

Editors: Aya Ishizaki (Fujoshi Club Writer Department) & Yutaka Fujiyoshi (BUNDO Inc.)