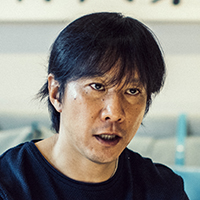

Edward Suzuki, an architect who has been independent for 35 years, continues to energetically create new works to this day. With deep knowledge in atomism, philosophy, and science, he also vigorously participates in triathlons and other sports. At the age of 65, his seemingly limitless energy and his mission as an architect were the focus of our discussion.

Profile

Vol.13 Edward Suzuki

Architect | Representative of Edward Suzuki Associates Inc.

Born in 1947 in Saitama Prefecture, Edward Suzuki graduated from the University of Notre Dame and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. After working with Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao, as well as Isamu Noguchi Studio in 1974, and Tange Associates from 1975 to 1976, he established Edward Suzuki Associates in 1977. He has worked on a wide range of projects including public facilities, private residences, and multifamily housing, such as the Saitama-Shintoshin Station, Shibuya Police Station Udagawa Police Box, and the Shimogamo House. Suzuki has received numerous awards including the Good Design Award and the Ecobuild Award. He also possesses deep knowledge in science, atomic structures, philosophy, and metaphysics.

※The titles and information provided are as of the interview date in July 2012.

Edward Suzuki passed away on September 15, 2019, at the age of 71. Upon hearing the news of his death, I was in disbelief, shocked, and my mind was filled with fond memories, such as playing basketball together and creating websites. I am truly grateful to have been able to preserve Mr. Suzuki’s philosophy through our interviews. I sincerely pray for his eternal peace. DK Sugiyama, Editor-in-Chief, “My Philosophy”

The Decision at Age 29

I established my office in 1976 when I was 29 years old. After graduating from Harvard University Graduate School, I worked at Tange Associates for 13 months. There, the work primarily involved presentations for big projects worldwide, and my tasks were mainly focused on design, preparing drawings, perspectives, and model making. Unfortunately, this didn’t allow me much opportunity to study actual design in depth. After much consideration about whether to move to another firm or to go independent, I decided to start my own practice. I thought, ‘I’m only 29, let’s give it a shot. If it doesn’t work out, I can always get a job somewhere else.’

The beginning was indeed tough. A friend and I rented a small office and shared a single phone line. We had only about 300,000 yen in capital. Back then, I was calling myself Edward Suzuki, which often led to humorous misunderstandings on the phone—people would ask if I was “Mr. Suzuki from Edogawa” (laugh). Realizing this was problematic, I eventually reverted to using my real name, Suzuki Edward.

My first project was a villa at Lake Yamanaka for a classmate from my alma mater, St. Mary’s International School. This project gained media attention, and fortunately, from there, work continued to come in through word of mouth. Before I knew it, 35 years had passed since I established the company in 1977. Over the years, the themes of my work have evolved. For over 20 years, one recurring theme, ‘Interface’, has represented the intermediate space between inside and outside. It involves incorporating traditional Japanese elements such as engawa (verandas), eaves, and tsubo-niwa (courtyard gardens) into contemporary architecture using new materials and designs. These are time-tested elements that have survived the era before mechanical energy, and I intend to continue exploring this basic theme in my future work.

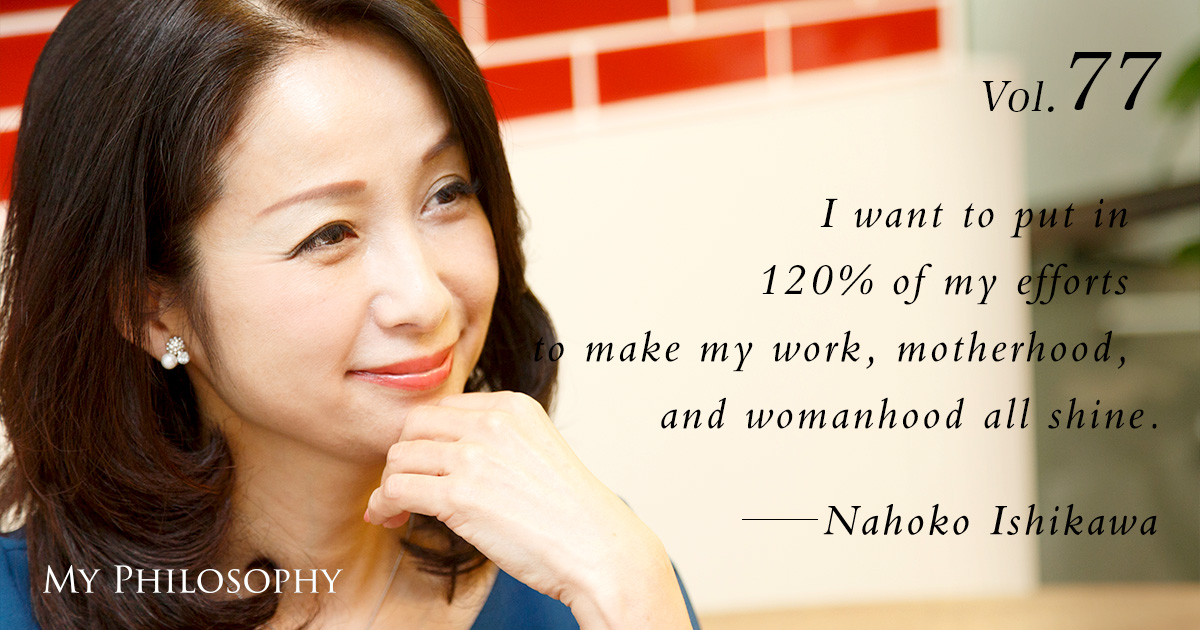

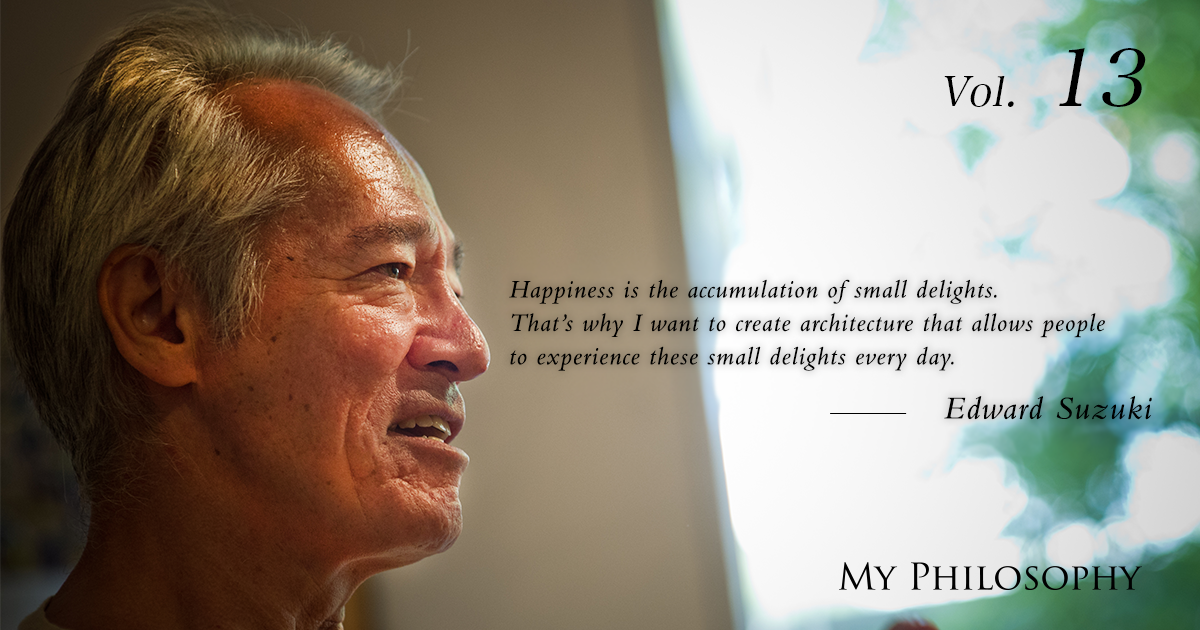

I Want to Provide Small Touches of Inspiration Through Architecture

At age 65, I’ve started to contemplate mortality. When I reflect on my life in my final moments, I wonder if I’ll consider it a happy one. It seems clear to me that humans live in pursuit of happiness. But what constitutes true happiness? It’s not necessarily about grand achievements like winning a Nobel Prize or an Olympic gold medal, but rather about accumulating many small, inspiring moments throughout life. As an architect, I strive to create these moments through the buildings I design, whether they are homes or train stations, ensuring that each time people interact with these spaces, they experience a fleeting moment of joy.

Particularly in residential design, where the stakes of daily life are centered, attention to detail is crucial. By maximizing the potential of an environment, even the smallest apartment rented by a young person with limited funds can feel like the most comfortable place in the world, just as much as a luxurious house built by the wealthy. The difference lies in realizing that potential, transforming the world through architecture. Unfortunately, many are still unaware of this potential. My mission is to harness the environmental potential surrounding individuals, regardless of their economic status, and to deliver happiness through architecture.

The Microcosm Unfolding from the Bathtub

For example, I might design a window that extends down to the top of the bathtub and create a small courtyard outside. This allows one to discover ladybugs strolling by or watch raindrops falling while soaking in the bath, spreading a world of small delights from the bathtub.

However, there was an incident where, despite the design specifying that the window should go down to the top of the bathtub, the construction company mistakenly built a concrete wall about 20 cm above the bathtub. I’m generally not one to get angry over minor mistakes, but I couldn’t let this pass. I understand that concrete cutting is a difficult task, but if I had simply let it go, the view that should have been possible would have been lost, and the small delights it was meant to bring would never be experienced. Maintaining attention to detail to give our clients those moments of delight is something I cannot compromise on.

Many architects may focus intensely on creating their works, but I believe it’s a mistake for architects to prioritize their vision over client satisfaction. Even if it wasn’t what they initially wanted, architects should prioritize the client’s satisfaction above all. It’s ideal when you can satisfy the client and also feel that you’ve created a good work of your own. Thankfully, since the establishment of my office, many clients have said they are happy they chose us and that everyone is happy because of our work, and I believe that’s because we always base our projects on client satisfaction first.

Encounter with Triathlon

At the age of 38, I decided to take up triathlon to rejuvenate my body, considering it a mid-life refresh. My interest in triathlon began when Shigeru Uchida, an interior designer I was working with, showed me photographs of a triathlon race in Hawaii. Being someone who loves sports, Hawaii, the sea, the sky, and festivals, I felt compelled to participate. However, the more I learned about it, the more I realized how demanding the sport was, and I initially gave up the idea. But later, at a party, an acquaintance, feeling my physique, suggested that I seemed well-suited for long distances and offered to train me. Emboldened by his flattery, I decided to give it a try under the conditions that I would not quit drinking and would only train for six months.

Ultimately, I’m glad I took on the challenge as it boosted my confidence. During my first participation in the Ironman Race in Hawaii, there was a moment when I was cycling downhill, completely alone. With the blue sky above and the shimmering sea on my right, I felt such happiness that I couldn’t help but thank the heavens.

Besides triathlon, I regularly swim three times a week, do strength training twice a week, and play basketball once a week. It’s clear to me that the mind is sustained by the body, and maintaining my physical health is crucial to continue my work in architectural design. I see it as the secret to my youth and plan to keep it up. My family cautions me not to overdo it and risk a heart attack, but I think dying doing what I love would be a kind of happiness in itself.

I met Edward during a basketball practice. Initially, given his age, I wondered if he could really play, but he was phenomenal (laughs). At that time, my own fitness routine was mostly anaerobic, so Edward had more stamina than I did. Most of our practice mates jokingly say, “I want to be like Ed when I grow old.” Witnessing a senior move so energetically gave me a clear image that continuous exercise could make this possible. Inspired by Edward, I too started swimming, running, and weight training weekly, keeping a vision of myself at 60. My participation in this year’s Tokyo Marathon was also influenced by him.

Edward is a gentleman who is kind to everyone and works hard at everything he does, which is something I aspire to emulate. The idea of “accumulating small delights” really resonates with me. I also want to transform small delights and joys into greater happiness. Edward’s statement that he still feels mentally like he’s 30 was very striking. With both a fresh mind and body, I hope to be like Ed when I’m 65.

July 2012, at Edward Suzuki Associates Inc. Writer: Mayumi Akiyama. Photographer: Daiki Ayuzawa