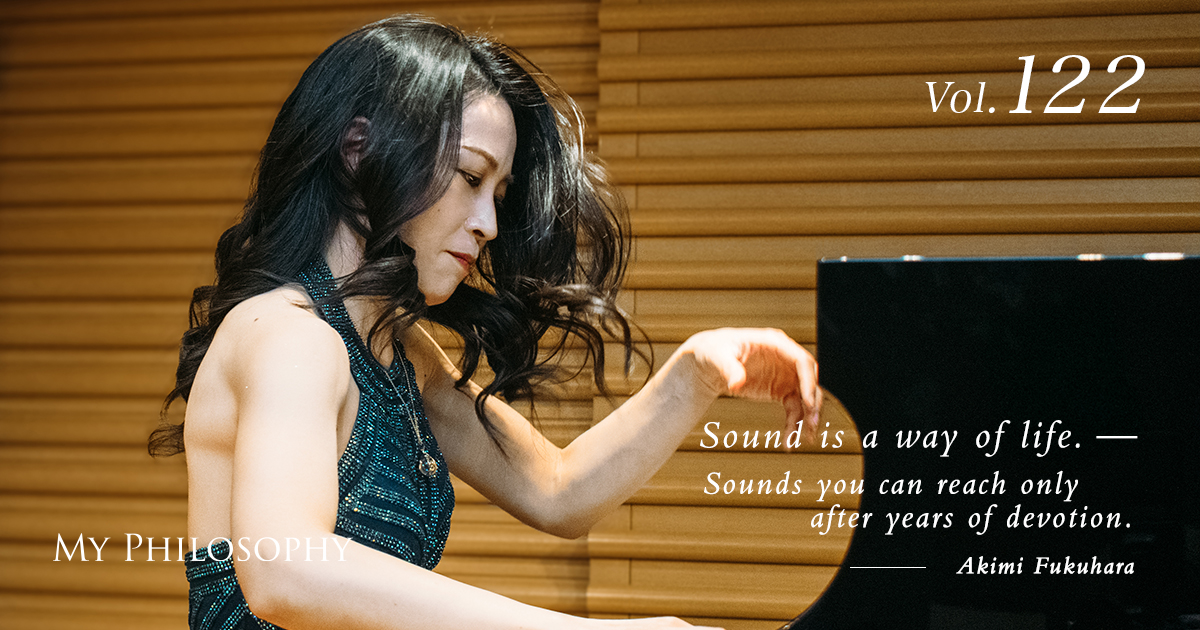

The moment she sits at the piano, something changes. Her gentle gaze sharpens, and each note is infused with spirit, reviving the composer’s intentions in the present day. This is pianist Akimi Fukuhara. Her life with the piano has always been propelled by one phrase: “If you are going to do something, give it your best.“

After making her recital debut at the age of 14, she moved alone to the United States at 15, going on to refine her artistry through the highly competitive programs of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and The Juilliard School—where only about seven pianists are admitted each year. In an era shaped by AI, what does it mean to be “real” in the end? We asked her for the answer.

Profile

Vol.122 Akimi Fukuhara

Pianist

Born in Osaka, Akimi Fukuhara gave her debut recital at the age of 14 at Hamarikyu Asahi Hall, with the live recording later released by Gakken PLATZ. After completing middle school, she moved to the United States to study at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and subsequently at The Juilliard School.

Her performances include appearances with the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra under Kazuyoshi Akiyama, the San Francisco Symphony Chamber Music Series, and the Metropolis Ensemble in New York. She has also collaborated with distinguished artists such as Christine Walevska, Nathaniel Rosen, and Pierre Amoyal.

A former CHANEL Pygmalion Days Artist, Fukuhara has recorded numerous albums over the course of her career. Most recently, she has released two albums in her Brahms series on the ACOUSTIC REVIVE label.

Alongside her performance career, she is deeply engaged in research on German Romanticism and historical performance practice, and has co-translated Performing Brahms (by Clive Brown et al.) and The Brahms Reader (by Michael Musgrave), integrating scholarly inquiry into her artistic work.

Official Website

https://www.akimifukuhara.com/

Raised by My Mother’s Words

My musical life began with a chance encounter. I was born into a family with no particular connection to music, but when we moved to an apartment building in Osaka when I was two years old, a piano teacher happened to live there.

Although it began as a simple extracurricular lesson, my mother’s words— “If you’re going to do something, give it your best.” —soon shaped my daily routine, and the piano gradually became the center of my life. She was strict, but she instilled in me the importance of persistence and steady progress. That mindset remains the foundation of who I am today.

As an elementary school student, I practiced relentlessly with piano competitions as my primary goal. Even when my family traveled, I brought sheet music with me—along with a handmade paper keyboard. There were times when I wanted to quit. I wanted to play like other children. But I kept going because the joy I felt when I played well was deeply rewarding. In hindsight, I think the piano truly suited me.

In the spring of my sixth-grade year, my father was transferred for work and we moved to Chiba. That marked a major turning point in my life. My new teacher told me, “You don’t need to enter competitions.”

Instead, under an educational philosophy focused on growth through deliberate challenge, I was trained intensively from the ground up—how to produce a good tone, how to touch the keys, and endless repetitions of scales. Every week, I spent hours rebuilding my fundamentals.

As a result, I performed at the age of twelve in a pre-concert at Suntory Hall for a recital by the world-renowned pianist Cyprien Katsaris *1.

Two years later, at fourteen, I held my official debut recital at Hamarikyu Asahi Hall, marking the beginning of my professional career. At that time, I simply ran forward, doing exactly what I was told. With the words “if you’re going to do it, give it your best.” etched into me, I was utterly focused on what lay right in front of me.

When I was fifteen, my mentor urged me on: “Go to the United States immediately. You should study with Professor Mack McCray in San Francisco.”

With that encouragement, I decided to leave Japan. It was at that moment that I resolved to live my life through the piano.

*1 Cyprien Katsaris A world-renowned French pianist celebrated for his exceptional virtuosity and wide-ranging repertoire. He is particularly acclaimed for his interpretations of Franz Liszt’s works and has received numerous international awards. Katsaris has performed at major concert halls around the world and is also known for his contributions to music education, mentoring young pianists internationally.

What I learned in America

I was never particularly articulate, and my English was far from fluent. In America, especially at first, I must have seemed like a strange, silent child—closed up like a clam. Rather than explaining things with words, my teacher in San Francisco chose a different approach: he played. He demonstrated at the piano and let me experience music directly, through sound.

My studies in America began with imitation—trying to absorb what I heard in my teacher’s extraordinary playing.

I graduated from high school early and entered the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, then later advanced to the graduate program at The Juilliard School. Juilliard’s piano master’s program is highly selective, admitting only around seven students each year. Pianists came from every corner of the world, each shaped by different cultures, backgrounds, and approaches to sound. No two players were alike.

The atmosphere in San Francisco was open and relaxed. Juilliard, by contrast, carried a sharp sense of intensity. In graduate school, we were required to do rigorous score analysis and academic writing, reading dense and demanding music texts. We examined musical structures in detail—how themes in sonata form develop, modulate, and return.

That training gradually became the foundation of my later research on Brahms*1.

*2Johannes Brahms (German: Johannes Brahms, May 7, 1833 – April 3, 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor. Together with J.S. Bach and Beethoven, he is often referred to as one of the “Three Bs” of German music. Born in Hamburg, he died in Vienna. Although his musical style is generally classified within the Romantic tradition, he showed a strong respect for Classical formal ideals. He is sometimes regarded as Beethoven’s successor; the conductor Hans von Bülow famously described his Symphony No. 1 in C minor as “Beethoven’s Tenth Symphony.”

Playing While Not Knowing

Around this time, my relationship with performance began to change. Playing was no longer about whether I could play, but about how deeply I understood. At some point, I entered a state in which I no longer understood the piano at all. I could no longer answer basic questions: What is good music? Where are the problems in my playing? How do I move forward?

Classical music is an act of bringing works written by composers who lived in the distant past back into the present. Playing with the illusion of understanding does not give life to sound. Unless a work is drawn deeply into oneself and performed as lived experience, it will never truly reach the listener.

That realization led me to translate every experience in my life into a dialogue with the piano. When I encountered beautiful landscapes, when I was exposed to different cultures in America, when I was deeply moved by books—I entrusted all of those emotions to the keyboard.

But it did not go as I had hoped.

Music cannot be confined within the framework of “correct answers.” Nor can it be optimized. I should not have been searching for a method to play better. Music is intangible—something you cannot grasp or see—born in a moment and disappearing just as quickly. That very uncertainty, that state of not knowing, was the reality I needed to confront.

A curious chain of encounters that began with a steak coupon

Even after graduating from Juilliard, I continued to base my work in New York. Life, however, is unpredictable—you never know what may happen.

One day, while shopping at a supermarket across from Juilliard, I was selecting vegetables at the salad bar when an elderly man I had never met before spoke to me.

“Don’t pick such wilted vegetables” he said, handing me a coupon for a steak.

The man was Leslie Dreyer*3, a former violinist with the Metropolitan Opera. Through him, I met the world-renowned cellist Christine Walevska*4 , and later had the opportunity to accompany her on her Japan tour.

Among those who came to hear that tour was Koji Amasaki*5 , who would later open the door to my research on Brahms. A single coupon picked up in a supermarket led to collaborations with world-class musicians—and ultimately to my present engagement with Brahms.

It feels almost like a modern version of the Straw Millionaire folktale. Guided by such mysterious and unexpected connections, I have continued to play the piano.

Then, in 2015, the most significant turning point of my life arrived.

My father passed away suddenly. It was a complete shock.

His passing led me back to Japan. When I think of my father, I realize I have no memory of ever being scolded by him. He always watched over me with generosity and calm. I believe it was the balance between my mother’s strictness and my father’s kindness that allowed me to continue with the piano.

Only after losing him did I truly understand the magnitude of his presence. Gradually, my activities in Japan increased, leading me to where I am today.

*3 Leslie Dreyer — An American male violinist. Born in 1930; died on August 6, 2019. He lived in New York for many years and served as a violinist with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra for 46 years.

*4 Christine Walevska — An American female cellist. Born in 1945 in Los Angeles. She studied with Ennio Bolognini at the age of eight and with Gregor Piatigorsky at thirteen. She made her first visit to Japan in 1974. In 1975, she became the first American musician to perform in Cuba under the Fidel Castro regime. She received high acclaim for her performance of Brahms’s Double Concerto with Henryk Szeryng. During the 1970s, she made numerous recordings for the Philips label.

*5 Koji Amasaki — Born in 1952, from Tottori Prefecture, Japan. While running Music Supply, a company engaged in the import, sale, and rental of musical scores, he has also worked as a translator of music-related books.

My Musical Anchor — Brahms

At that time, my greatest musical support came from Johannes Brahms, the 19th-century German composer. Brahms confronts the depths of human inner life and contradiction, yet his spirit never collapses; there is a quiet strength in his ability to stand firm. His music is not flamboyant, but it is profoundly mature—grounded, steady, and deeply human.

That quality resonated with me deeply. A pure sense of wonder—How could something so beautiful possibly be created?—became the force that sustained my daily practice. Since returning to Japan, I have continued to play Brahms without interruption.

Recently, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to translate a substantial scholarly work: The Brahms Reader, published in Japanese in two volumes. The Truth of Brahms (Vol. I) and Brahms: 150 Years of Reception (Vol. II) by Michael Musgrave (Ongaku no Tomo Sha). The book reexamines Brahms’s life from fresh perspectives, reconsidering the path he took as a nineteenth-century composer. It also traces how Brahms was received and evaluated over a span of 150 years—from 1850 to 2000—revealing the shifts in his reputation across generations.

Often described as a new landmark in Brahms scholarship, this work allowed me, through the act of translation, to gain a far deeper understanding of the stories embedded within his music.

In parallel with this translation project, I was preparing my latest album, the second in my Brahms series: Piano Sonata No. 3 – The Origins of a Young Composer (ACOUSTIC REVIVE) . The first album, released seven years ago— Brahms: Piano Pieces – The Love Embedded in the Music of a Solitary Composer— focused on the late piano miniatures, often described as a microcosm of Brahms’s late years. In contrast, the new album explores the very roots of his musical language, featuring works from his youth, including piano sonatas, variations, and songs.

-

-

Akimi Fukuhara — Brahms Album II

Brahms: Piano Sonata No. 3

— The Origins of a Young Composer —

ACOUSTIC REVIVE

Release Date: November 24, 2025

Both albums were recorded by ACOUSTIC REVIVE (Sekiguchi Machine Sales Co., Ltd.), a company renowned for producing high-end audio cables and equipment designed for the highest level of sound reproduction. Guided by the concept of “preserving the finest possible sound,” the recordings were made not in a studio, but in a concert hall, capturing its natural resonance as if sealing it in a vacuum, using an exceptional array of recording equipment.

For this project, I also had the privilege of performing on a beautiful C. Bechstein piano. Making full use of the clarity and refinement of today’s Bechstein, I sought to express the sound and atmosphere of the era in which Brahms lived. I explored tuning systems that are more true to the sound of the 19th Century when Brahms composed these pieces. From selecting the venue to choosing the microphones, the process took several years, culminating in a work brought to life through close collaboration with the production team.

Among the recorded pieces, my personal favorite is the piano solo arrangement of the song An eine Äolsharfe (“To the Aeolian Harp”). With the generous cooperation of the Brahms Institute at Kiel University, I received the score and was able to make the world’s first recording of this version. It is a piece of breathtaking beauty—one that deeply stirs the heart.

The most demanding piece to record was Piano Sonata No.3. It is a work that requires such physical stamina that, at times, I felt I might not be able to play it at all. Although piano playing may appear elegant, it is, in reality, an extremely demanding form of physical labor.

During performance, my heart rate rises to an almost unbelievable level, and it is not uncommon for me to lose two to three kilograms by the time a concert is over. In order to produce sound, I play not only with my fingertips, but with all the strength in my arms and my back, engaging my entire body and spirit.

Because of this, daily physical maintenance is essential. Managing my body like an athlete is an important part of continuing to perform professionally over time.

What I would Tell My Fifteen-year-old self

I often find myself thinking about how short life is. The more I learn, the more I realize how much I do not know. And yet, there is joy in that realization.

After starting a family, I could no longer spend entire days at the piano as I once did. And yet, unexpectedly, my thinking about music became freer. This was something I never anticipated. I felt a quiet release—as if I no longer needed to push music into a corner or overthink it beyond necessity.

If I were asked what I would tell my fifteen-year-old self, my answer would be simple: It is a long road.

There are no shortcuts, and there is no way to make it more efficient. That long journey—doubts and inner struggles included—is precisely what creates a kind of “real” sound that only humans can produce, something that AI can never replicate. There is no need to rush.

There will come a moment when the long-held sense of uncertainty suddenly dissolves. A hurdle that once seemed impossibly high will already have been crossed before you even realize it. We don’t have control over when these breakthroughs come.

That is why I would want to tell my younger self: build endurance, accept uncertainty, and never give up.

There are a few rare pieces that feel as though they were written to confront something essential in the human experience. And for such works, there is a way of performing them that does not merely interpret the music, but embodies its underlying philosophy. This is what I am pursuing.

Music is never completed alone. Encounters with mentors, the musical support I found in Brahms, the presence of my family, and those who listen to my performances—countless connections have carried me to where I am today.

When I play the piano, I stand as a very small medium between past and future. If the sound I create can move something—even slightly—within those who listen, that is my wish today.

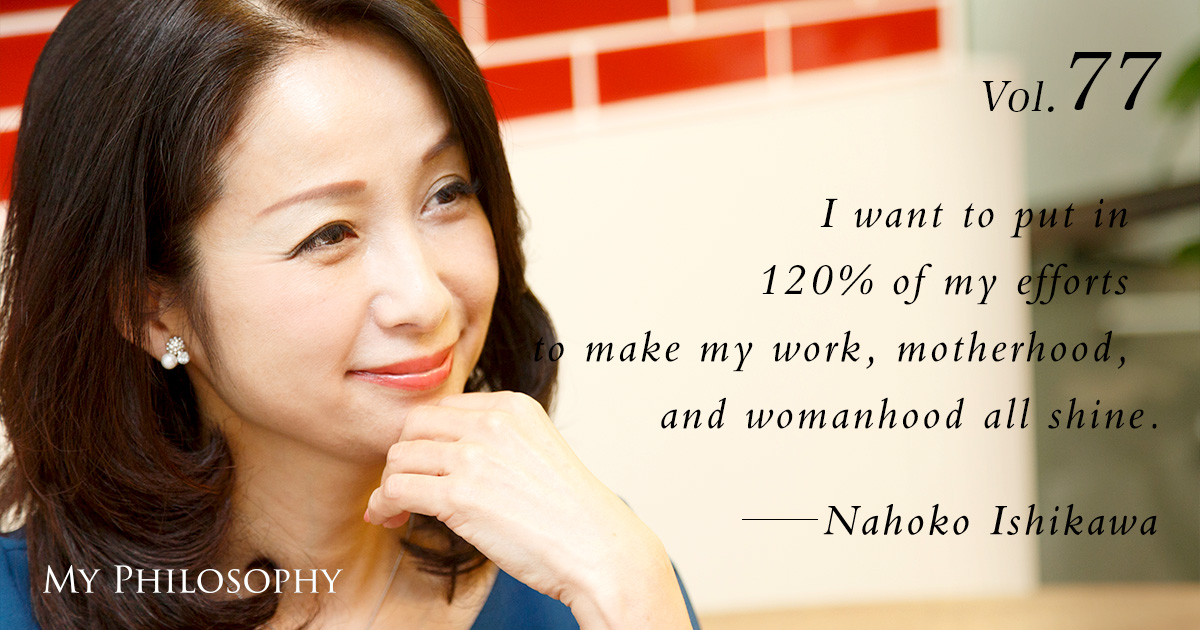

Having seen so many distinguished figures appear on My Philosophy over the years, I must admit I arrived feeling a little nervous, wondering whether I was truly worthy of being featured myself. However, as Mr. Sugiyama posed one thoughtful and concrete question after another, time simply flew by before I knew it. Thank you, Mr. Sugiyama, for taking such a genuine interest in my musical life. It was truly a delightful experience.

I first met Mr. Sugiyama last year at a celebration marking Mr. Tomio Taki’s 90th birthday, where Mr. Taki kindly introduced us. Being able to meet Mr. Sugiyama and be interviewed by him at this particular moment in my life felt like a real gift. There were so many things I could finally put into words because it was now, and I honestly feel that without Mr. Sugiyama’s passion and energy, I would not have been able to speak so openly and honestly in my own voice.

Through the interview, I came to a simple realization: I have never been able to separate my life from the piano. Ah—so I really did just love the piano that much! It suddenly made perfect sense (laughs).

What left a strong impression on me was how, even before the interview, Mr. Sugiyama was already thinking ahead, saying, “There are many quiet photos of you —we need shots that truly convey your performance.” He had clearly considered what kind of images I needed and shared idea after idea. I was genuinely moved by how deeply he had thought it through. He is someone who generously shares his overflowing energy with those around him, naturally uplifting and brightening everyone in the process. It’s something I personally cannot do, and I truly respect him for it.

Inspired by Mr. Sugiyama’s power, I, too, want to move forward with courage—DoDoDoDo!

Thank you so much for such a wonderful time. Let’s definitely play a piano duet together again!

Pianist Akimi Fukuhara

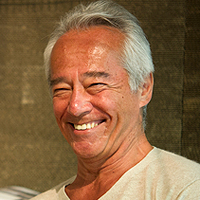

The atmosphere changes the moment Akimi Fukuhara sits at the piano. Her calm presence transforms instantly, and her sound seems to take on a soul—this dramatic shift is, to me, one of her greatest charms. Experiencing her performance live was overwhelming; I was completely captivated by the tension at the very moment the sound rises, and by the strength that lies beneath its beauty.

In this dialogue, she spoke candidly not only about her exceptional sensitivity, but also about the real process she has walked through—accumulation, hesitation, and living alongside uncertainty. It was a rare opportunity to encounter professional insight that goes beyond pianistic technique, revealing the thought, life experience, and resolve that exist behind the music.

For those who have not yet heard Akimi’s music, I strongly encourage you to pick up her CD. There is an authenticity that words simply cannot convey. Having concluded this interview, I am convinced that Akimi will continue to quietly yet powerfully move the inner world of those who listen to her music.

To the staff of Bechstein Centrum Tokyo, thank you very much for allowing us to conduct this interview in such a wonderful hall. It was my first time experiencing a Bechstein piano, and I was deeply moved by its beautiful tone. Sharing a four-hand performance of a beginner’s piece with Akimi has become a cherished memory. I sincerely wish you continued growth and success.

Editor-in-Chief, “My Philosophy” — DK Sugiyama

With the kind cooperation of: Bechstein Centrum Tokyo

Bechstein Centrum Tokyo is ideally located with direct access from Hibiya Station on the Tokyo Metro Hibiya Line, offering exceptional convenience in the heart of the city.

Bechstein Centrum Tokyo features both a showroom and a hall/studio, allowing us to respond more precisely to a wide range of customer needs and to provide an even more comprehensive level of service.

The showroom displays key models from C. Bechstein and W. Hoffmann. The hall and studio can be used for a variety of purposes, including recitals, concerts, private practice, and lessons. Experience the transparent, richly colored sound that is unique to Bechstein pianos.

Address: B1, Hibiya Marine Building, 1-5-1 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0006, Japan

Business Hours: 10:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m. Closed: Wednesdays

Phone: +81-3-6811-2925 (Showroom) +81-3-6811-2935 (Hall & Studio)

Access: Direct access from Hibiya Station (Exit A9), Tokyo Metro Hibiya Line / 5-minute walk from Yurakucho Station (Hibiya Exit), JR Yamanote Line

January 2026, Interview conducted at Bechstein Centrum Tokyo Saal (Hall)

Interview & Editing: DK Sugiyama

Project Manager: Chiho Ando

Text: Eri Shibata (Deputy Editor, My Philosophy)

Photography: Hirona Goto