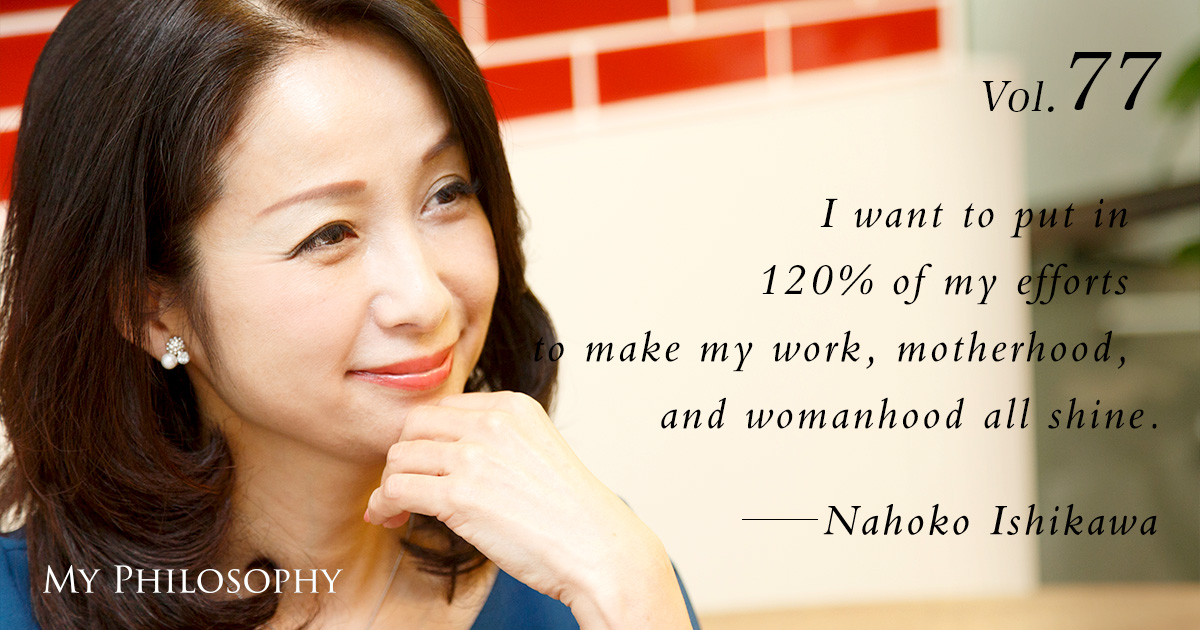

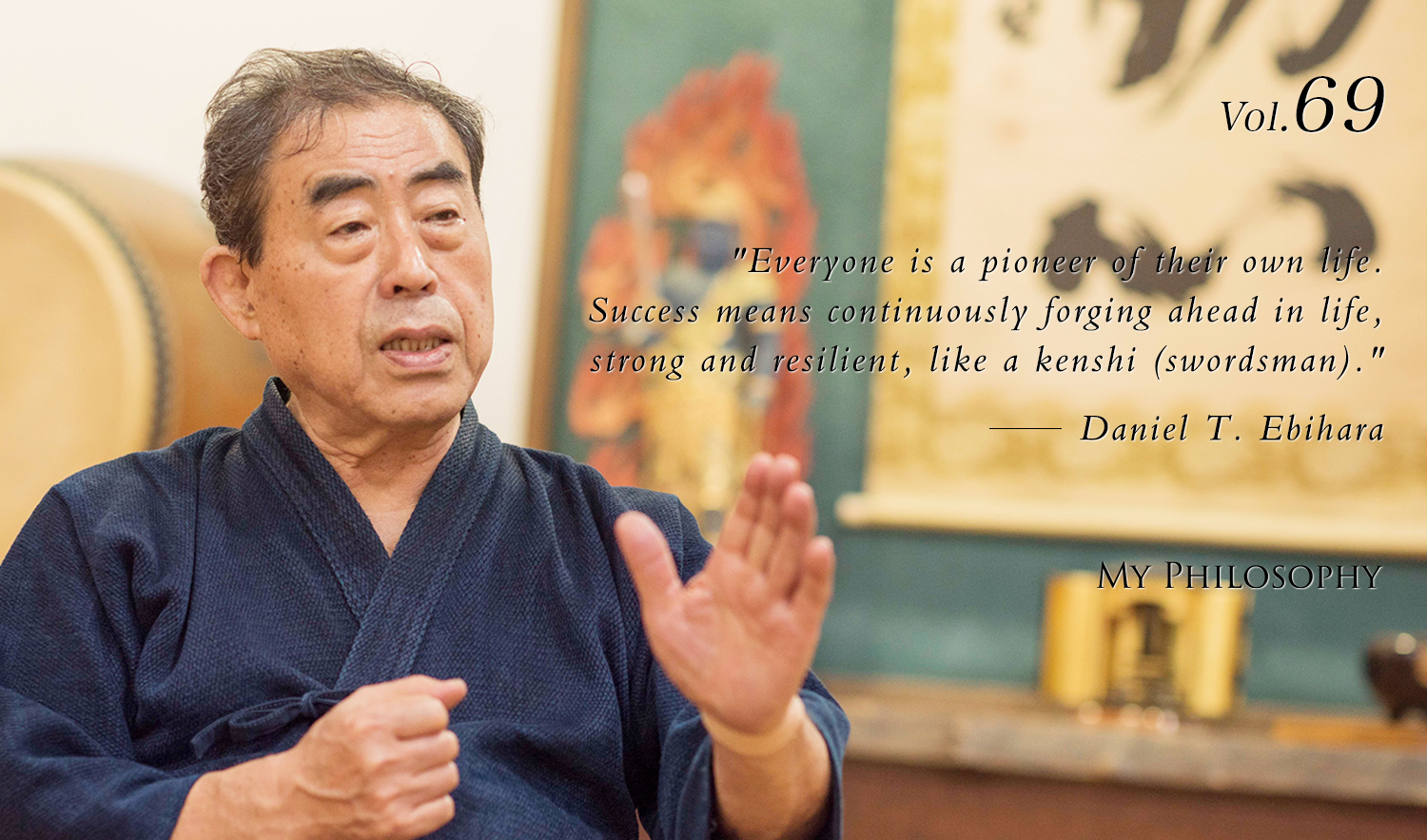

Daniel T. Ebihara, the head of the 'Ken Zen Dojo' in New York, continues to impart the spirit of the sword. After graduating from high school, he moved to the United States alone, expanding his network while changing jobs one after another. He shared with us his life story, reminiscent of the Straw Millionaire, as he continued to forge ahead in life and achieve success in real estate.

Profile

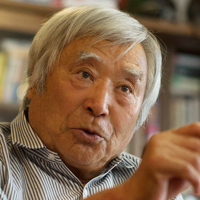

Vol.69 Daniel T. Ebihara

Head of the New York Kendo Dojo, Entrepreneur, and Product Designer

Born in Tokyo in 1938, he lives in New York City. After graduating from Aoyama Gakuin (high school), he came to the United States by himself. He dropped out of Hunter College in 1959 and dropped out of Columbia University in 1961. Learning English through teaching judo, he expanded his network and polished his business sense as he wandered through some 56 different jobs. After working for his father's import business, he entered the real estate industry, obtained his broker’s license, and went out on his own. He is ranked 7-dan in kendo.

I want to carve out my own path

I was born in Asakusa in Tokyo. I came to America promptly after graduating from Aoyama Gakuin. I am often asked, “Why did you not go on to college from there?” The reason is I felt misgivings about the well-trodden path. Rather than the typical main road that anyone would envision, I chose the less-crowded back road, by which I could get to my destination in my own way, as I wanted to get there on my own. For me, this “destination” – also my strong wish – was to somehow surpass my father. I disliked being called “the company president’s son” and had an intense desire to “carve out my own path in life, under my own power.”

My father had become independent at around 14-years old. His company made the artificial flowers that women pinned to their clothes. During the war, he had large factories in Manshu (occupied Manchuria) and Korea. When I said I did not want to go to college, he told me, “Do as you like. When I was your age, I managed 2,000 people. If you’re my son, you can do it too – but go do it after you graduate high school.”

So, after attending my high school graduation ceremony, I said, “Now, I will leave home,” and I went to the United States. My father gave me a parting gift of $500 in cash – at that time enough to eat for around two months. With this gift in hand, I got a ticket for a ship on which I would also supervise a shipment of my father’s export goods. Though I said it was my “leaving home,” my father gave me this supportive push to help me carve out my own way under my own power.”

Budo widened my world

I had no English ability at all when I came to the US. It was not that I was merely “incapable,” but rather that I had held misgivings about the teaching methods of English in Japan. A baby born in the English-speaking world learns to speak the language naturally, without being taught, and so I thought that, rather than studying English in Japan, I should just go! Learning English was the first thing I did after arriving in the US. Accordingly, I think that the “go, then learn” approach was right for me.

The US back then was in a judo boom, and the YMCA coincidentally reached out asking for a judo teacher, and I suddenly found myself with a number of disciples. Through that opportunity, I began teaching at a recreation center in Brooklyn, and thereafter my world and network would expand more and more, through teaching at well-known places such as the New York Athletic Club, where celebrity businessmen gather. One of my new contacts at the time, an Olympic fencer, invited me to a party and, at the party, asked if I could do kendo. We held a match for entertainment’s sake, and I sent the fencer flying with a “tsuki” (thrust) technique. Afterward, the opponent asked, “please teach me!” This was the start of Ken-Zen Dojo.

Turn a crisis into an opportunity

Additionally, I worked as a carpenter and a taxi driver, any sort of work. Looking back, I worked no fewer than 56 different kinds of jobs. I even worked in Alaska, but eventually began to long for working in business, out of my urge to “surpass my dad.” To start in business, though, I would need a good deal of money, so I decided to accept my dad’s request that I help him with importing the products made in his factories. No sooner did I begin this work than a port workers’ strike occurred, making it impossible to receive the deliveries, despite the ships arriving. The products were season-specific Christmas decorations so, despite originally having customers, the orders were all cancelled due to the holdup.

My father’s company had already received its loan from the bank, and I was merely being made to wait at the port. Christmas was approaching, and I thought that the only way to get through this would be to sell products on a retail basis. So I rented out one storefront in Harlem, brought our products in and began retail sale, without even constructing display shelves and merely hanging samples from the ceiling by strings. The products did not sell at all, even with as little as two months remaining until Christmas. Despite becoming friendly with a local African-American resident who happened to enter the store to drink water and meeting various important Harlem figures, the products would not sell. I thought I might have to commit seppuku and die in front of the bank. Amid that stress, I suddenly realized the reason the products were not selling: the Christmas dolls were all painted with white skin color and being sold in Harlem, an African-American community. The products began to sell after I painted the skin black. Then, the week before Christmas, right around the time when bonuses are given out, sales suddenly soared. In the end, I brought in multiple times as much money as wholesale, and we were able to pay off the bank loan without issue, but from this experience, I felt from the bottom of my heart that trading in merchandise was not a good fit for me.

With my remaining money from the Christmas decoration sales, I started in real estate. I bought two buildings, but, not knowing my left from right in the new industry, I went to work at a real estate company and learned the ropes. Thankfully, I was able to bring about big profit at the company, the company’s president served as my sponsor, and I obtained my broker’s license. This became a huge turning point in my life, after which I met the likes of Harry Helmsley, famous in the industry, and the current president Donald Trump, and I was able to completely pay off the debt on my buildings. With the profit from my buildings, I have been able to operate several dojo and have a comfortable living.

To live as a kenshi, as a pioneer

I took the name Daniel from the American pioneer figure Daniel Boone. Even though Daniel was someone who reasonably could have become president, he retired and committed himself to aiding George Washington, living in a small village in Kentucky. In other words, he did not think of becoming famous or rich. He was a person who lived simply for the happiness of others. I also wanted to be such a person, in addition to longing to surpass my father. That is why, when I obtained US citizenship, I took on the name of this figure I held as ideal. I want to keep being the pioneer of my own life.

I think that there is no failure, be it in life or in business. Even if I fail, I move on quickly to the next thing so that it does not end up being a failure. In Japan, there is the proverb, “ju yoku go wo seisu” or “softness ably subdues hardness.” This can be applied to both business and life. That which is flexible can skillfully deflect a sharp spearhead and attain victory. When one is fighting with the intent of doing in his enemy, his soul closes up, but the chance for victory appears precisely when one is open, with an attitude of, “by all means, please come from any direction.” One cannot win if he is always fighting. Nor should one strike when his opponent has withdrawn and has his guard down. If, flexibly, like a willow tree swaying in the wind, one observes matters from above and goes with the flow of the situation, the path that one should take will always reveal itself.

“What a cute little boy! When I asked him where he came from, he said, ‘I am a child of the light of the future, I flew here with the light.'” Just like the adorable child reminiscent of a Sony commercial song, Daisuke Sugiyama still seems to be in pursuit of new things. I believe his projects can offer dreams and hope to readers. I expect him to continue being a “child of the light of the future,” guiding humanity in new directions. He is a person who inspires hope that he might bring together this world, shattered into pieces by the Big Bang.

Head of the New York Kendo Dojo, Entrepreneur, and Product Designer

Daniel T. Ebihara

When I was in elementary school, I started practicing kendo in New York and met Mr. Ebihara. This was about 30 years ago. Even as a child, I remember being struck by how impressive he was (laughs). Whenever I visited New York or when he returned to Japan, he would offer me various pieces of advice. When planning the New York series of “My Philosophy,” I wanted to share Mr. Ebihara’s impactful ideas with many people, which is why this project came to be. Mr. Ebihara is an excellent storyteller with a very positive mindset. When I started my company, he advised me, saying, “All kinds of work and experiences are like rivers. When many rivers merge, they eventually become a great river. Put all your effort into each job and encounter to create many rivers.” This advice has helped me create many rivers. The interview with someone who has supported me since my elementary school days has become a wonderful memory.

September 2017, At Kenzen Dojo, New York Writer by:MARU Photography by:Sebastian Taguchi