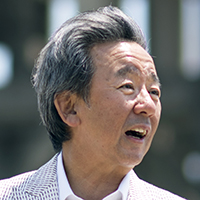

Mr. Kiyoshi Kurokawa, who has been active in various fields such as healthcare, education, and policy, shared his insights on what is necessary for Japan's education system as we enter a new era, drawing on his extensive experience abroad.

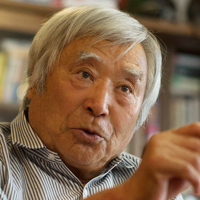

Profile

Vol.94 Kiyoshi Kurokawa

Doctor of Medicine | Honorary Professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies | Representative Director of the Health and Global Policy Institute

Born in 1936, he graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Tokyo. He has held numerous key positions, including Professor at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine; Professor and Professor Emeritus at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo; Dean and Distinguished Professor at the School of Medicine, Tokai University; President of the Science Council of Japan; Member of the Council for Science and Technology in the Cabinet Office; Adjunct Professor at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, University of Tokyo; Special Advisor to the Cabinet; and Chairman of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission (NAIIC) by the National Diet of Japan.

His major works include "Building a World-Class Career (Sekaikyu Carrier no Tsukurikata)" (co-authored, TOYO KEIZAI INC.), "Revolutionizing University Hospitals (Daigaku Byouin Kakumei)" (Nikkei Business Publications, Inc.), "The Innovation Mindset (Innovation Shikoho)" (PHP Shinsho), "Captive to Regulation (Kisei no Toriko)" (Kodansha Ltd.), "Why Organizations Without Dissent Are Wrong (Naze ‘Iron’ no Denai Soshiki wa Machigaunoka)" (commentary, PHP Institute, Inc.), among others.

The Stagnant Growth of Japan in the Heisei Era

Throughout the 30 years of the Heisei era, Japan’s economy has not experienced real growth in dollar terms. This period has seen significant global changes, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, ending the Cold War, the dawn of the Internet age, and the recession of Japan’s bubble economy from around 1991 to 1997. In 1995, Japan faced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, the Tokyo subway sarin attack, the assassination attempt on the National Police Agency Commissioner, and the Jusen problem (the collapse of Japan’s home mortgage lending industry), followed by the shut down of Yamaichi Securities in 1997. Did you know that the Los Angeles earthquake occurred on January 17, the year before the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, on the same date? Watching the footage of collapsed highways in Los Angeles, there were mocking comments like, “Such a thing could never happen in Japan.” Yet, the following year, the same disaster occurred, revealing the “iron triangle” of bureaucracy, industry, and politics, along with the shoddy construction practices of general contractors. It felt like divine punishment for those who had laughed at others. Subsequently, accidents like falling concrete blocks within Shinkansen tunnels occurred one after another.

The fundamental issue with Japan’s lack of economic growth over these 30 years is its unique vertical society, which makes horizontal movement difficult, characterized by mass hiring of new graduates, lifetime employment, seniority-based promotion, and a culture where “Yes-men” refrain from voicing concerns or dissent, all for the sake of personal advancement or self-preservation. This stands in stark contrast to accountability, which involves listening to various opinions as someone in a position of authority and making and executing decisions responsibly. The term “accountability” itself becomes a classic case of “lost in translation.”

Among those involved in the Tokyo Metropolitan Government building parcel bomb incident carried out by Aum Shinrikyo was one of my students, a medical intern who graduated from the University of Tokyo Faculty of Medicine. A year before the incident, despite having a year left in his training, he expressed a desire to quit because he had something else he wanted to do, which he refused to disclose. Based on his personality, I had assumed he might want to pursue theater or music, but it was unfortunate that he ended up committing such a crime. Why would intelligent individuals commit crimes? It might be because they spent their entire education focusing solely on getting into high-scoring schools without developing social skills. The fact that Aum Shinrikyo had many highly intelligent members from top universities was shocking and made me feel responsible. It led me to question the myth centered around academic achievement.

What Higher Education Should Be

It’s a rather unfortunate situation that in Japanese universities, students aren’t really required to study much after gaining admission. Moving forward, real ability will start to be challenged more rigorously. In the entrance examinations for Oxbridge, questions such as “Why are there no mountains on Earth taller than 10,000 meters?” are posed to evaluate the logic of the candidates’ responses. At top American universities like Harvard, Princeton, and Berkeley, students are required to read works by Plato, Aristotle, Machiavelli’s “The Prince”, Marx, and others. About 90% of the classes are dedicated to discussions about the content, and you can’t participate unless you’ve done the readings, which means the volume of study required is immense. In Japan, the approach to learning about Plato, for instance, might be more about listening to a lecture by a professor.

Those with experience studying at Oxbridge have told me about being required to read around ten books a week and then write their opinions in a few pages with a ballpoint pen to present to their “tutor.” Many say they’ve never had to use their brains so deeply before. Being able to quickly grasp the context of an issue, frame your own thoughts, organize those thoughts, and articulate an opinion is critically important. Japan tends to approach issues from a contemporary standpoint without considering context or framing, leading to discussions that just oscillate between “yes” and “no.” It’s been said that the only place where the talents of University of Tokyo students are utilized is on quiz shows, but at this rate, they will eventually be surpassed by computers. Engaging in discussion and thought using knowledge is the essence of higher education. As Winston Churchill once said, “The first duty of a university is to teach wisdom, not trade; character, not technicalities.” Knowledge and wisdom are different; the wisdom learned from history is crucial. Japanese individuals who have only accumulated knowledge will find it hard to compete with the true elites from abroad who have experienced a culture of critical thinking and conceptual understanding.

Viewing Japan from Outside

Going abroad allows one to relatively perceive the strengths and weaknesses of their country’s national character and culture. For instance, Yukichi Fukuzawa, who brought back many books from Britain, deciphered them himself, and authored several works to introduce them, the Iwakura Mission, the Choshu Five, the Satsuma Seven, Kenjiro Yamakawa, and Kanichi Asakawa, whom I mentioned in the introduction to the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission report, chaired by me, are all examples of individuals who went overseas to learn since the Meiji Restoration.

The essence of things is not easily grasped by merely watching TV or experiencing travel abroad and feeling as if one has truly been there. What shapes the human heart is “real experience.” It’s vital to actually go out into the world, preferably on a personal basis, to see, feel, and meet various people with one’s own eyes. Going abroad allows you to see Japan in relative terms, to feel, to recognize its weaknesses, and to foster a healthy sense of patriotism.

Independent Life

In recent years, the number of people living to 100 has increased. Women start to experience a decline in health around the age of 60, and men around the age of 70. However, it appears that a small percentage of men remain almost unchanged until they reach 100. According to research by Hiroko Akiyama of the Tokyo University Institute of Gerontology, the characteristic shared by men who remain relatively unchanged until 100 is independence.

I have had the opportunity to change locations and affiliations, meeting various colleagues and friends. After over 14 years of university life in America, I left the University of Tokyo before reaching retirement age, something unimaginable at one point, due to an invitation to become the Dean of the School of Medicine at Tokai University. Had I not left, I might have eventually been offered the position of director at a public hospital. However, having met several “role models” in America and being mentored by many, I had a strong desire to remain in the field of education. Upon returning to Japan, I realized I could genuinely care for my students. Without the experience of being mentored by excellent mentors, I don’t think one can become a good educator. The foundation of education is repaying the favor. I hope young people will find their role models and develop a concrete vision of the kind of person they want to become. If they cannot find it in Japan, in this era, it’s beneficial to study, work, or join an NPO abroad in any form at a young age. You will feel yourself changing. You can always return to your homeland.

Daisuke Sugiyama has been a bright and proactive young man I’ve known for about seven years. We meet occasionally, but he keeps me updated with exciting plans or events via email. I had heard about the “My Philosophy” project a long time ago, and he is always involved in moving various unique projects with interesting people.

The interview progressed with his brisk tempo from the setup and concluded with a shift to the topic of “Carpe Diem – Seize the Day.” That night, I received an email from him saying, “This interview was about ‘independence’ and ‘Carpe Diem’, , living for today.'” He has a knack for capturing the essence, and his actions and work are swift. He is bilingual in Japanese and English, and values his family highly. Let’s do something together again.

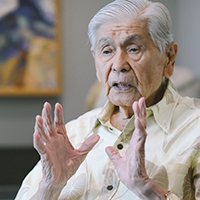

Dr. Kiyoshi Kurokawa

Interacting with Dr. Kiyoshi Kurokawa, who is 82 years old, one could easily come to believe that “age is just a number.” He always maintains an excellent posture and is impeccably dressed in a suit whenever we meet. During the interview, while discussing events from the Heisei era, we were able to have fascinating conversations about the changes in Japan and the world. Dr. Kurokawa mentioned an anthropological notion that a village without any contact with the outside world could perish, but the presence of even one person connected to the outside world could ensure its survival. Staying in one place tends to limit our perspectives, but venturing into different places can enable us to view things from multiple angles.

Having spent a formative period in New York, I was able to objectively appreciate the virtues and marvels of Japan. Despite the many positive aspects of Japan, the global environment is constantly changing, prompting me to think that it is essential to have one’s own principles while being adaptable and continuously updating oneself. Inspired by Dr. Kurokawa’s “independent” mindset and his approach to “living for today,” I am motivated to cherish each day and take actions step by step.

February 2019, at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS)