Michelin's Bib Gourmand for three consecutive years, and hailed as an "Italian that brings excitement" restaurant, Azabu Juban's popular establishment 'Ristorante La Brinca' is helmed by owner-chef Yoshiyuki Okuno. Known for his delicate yet bold and creative dishes that fully utilize the potential of each ingredient, he continuously embarks on new business ventures. We had the opportunity to discuss what drives this power and the reasons behind his transition into the culinary industry, making him one of the most dynamic chefs today.

Profile

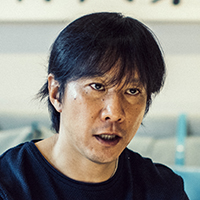

Vol.60 Yoshiyuki Okuno

Owner-Chef of Ristorante La Brinca

Born in Osaka Prefecture in 1972, Yoshiyuki Okuno was raised as the son of a kaiseki (traditional Japanese multi-course) restaurant owner in Wakayama. He went to the United States to study business management. After graduating from an American university and gaining nearly two years of experience as a company employee in Japan, he transitioned to the culinary industry. He trained himself at an Italian restaurant in Tokyo before moving to Italy at the age of 28. There, he honed his skills at Michelin-starred restaurants across eight regions, including Liguria and Piedmont, before returning to Japan. In 2003, he opened "Ristorante La Brianza." While continuously offering Italian cuisine from across the country with a unique perspective and solid technical skills, he also strives to create a restaurant that extends the concept of "home cooking," which is at the heart of Italian cuisine. His restaurant is beloved not only by local residents but also by foreigners and staff from the Italian Embassy. Currently, as the owner-chef of three establishments, he is involved in a wide range of activities, including food production, cooking instruction, and restaurant production overseas.

*Titles and other details are as of the time of the interview (July 2017).

A Small Defiant Spirit and Great Curiosity

In 1972, right after I was born in Osaka, my parents opened a restaurant in Wakayama. The world had just shifted from rapid economic growth to a more stable growth phase, and our restaurant, which was a hybrid between a family restaurant and a café, was quite unique in Wakayama City at the time and became very popular. Four to five years later, with the onset of the economic bubble, my parents opened a kaiseki restaurant in “Arochi,” Wakayama’s largest entertainment district. The restaurant was on the first floor of the building, and our home was on the second and third floors, so I grew up in an environment where I was constantly surrounded by food, eating at the restaurant when I was hungry and earning pocket money by helping out as a part-time job.

My father believed that everything was a learning experience, so he exposed me to the “best of the best” that business and cultural elites favored, such as dining at “Kitcho” or staying at “Gora Kadan.” Even as a child, I could sense how remarkable these experiences were, though I remember thinking, “I would’ve preferred a place with a waterslide pool” (laughs).

During my teenage years, I had a bit of a rebellious streak against my father’s teaching that “being the master of even a small domain will be your education.” I became obsessed with “creating something with my peers and achieving it together.” I participated in national kendo tournaments several times, but it was mostly team competitions. I thought, “After all, what you achieve with your comrades is precious.” Also, although I attended a school known for its high academic standards, my desire to leave home was very strong. So, without telling my parents, I secretly expressed my desire to “find a job” on my career preference form.

As I began receiving offers from several companies, my teacher, recognizing my reasonably good grades, suggested to my parents that I should go to university. I wanted to get a job, so I thought, “Mind your own business!” But the suggestion was to study abroad in South Dakota, in the Midwestern United States—a place I had never heard of. Of course, it would allow me to leave home, and it sounded exciting, right? (laughs). I totally fell into my teacher’s plan. I took the TOEFL while staying with a host family and enrolled in a university. I spent my entire time in South Dakota at the same school, without transferring anywhere else.

Better to be the Head of a Sardine than the Tail of a Sea Bream

After returning to Japan, I joined a Japanese company. As a salaryman, I quickly realized, “No matter how much I work, I can never truly reach the top.” Of course, “the top” can mean different things in different contexts. In the sense of being a business owner, I am at the top now, but in a restaurant, the true top is the customer. I now understand that suppliers and supportive colleagues are “partners, not subordinates,” but the idea of “even if it’s small, strive to be at the top” was deeply ingrained in me from my upbringing and was something I couldn’t shake off.

While I can’t say that I “understood everything” during my short 1 year and 8 months as a salaryman, I did come to the realization that I wanted to “take full responsibility for myself.” I felt a strong sense of discomfort in an environment where you could blame someone else or escape with a casual “don’t worry about it.” I had a powerful desire to “do something on my own!” However, I was just an immature adult in my twenties, and after such a short time in the workforce, I hadn’t yet developed any talent that others would recognize. During that time, my interest naturally gravitated towards the thing I was most familiar with—cooking.

The reason I chose to pursue Italian cuisine was simply because I thought it was cool (laughs). First, I trained for about four years at the Italian chef’s restaurant in Japan. He was the first Italian chef to open an Italian restaurant in Japan. Then at the age of 28, I headed to Italy. It was crucial to properly observe and learn from the culture, the people, and everything that needed to be learned. I believe that if you don’t know the real thing or the authentic way, you’ll start to lose your way as you advance further.

When people ask me, “Okuno-san, your cooking is very creative, and you use Japanese ingredients—can you really call this Italian?” I can confidently say, “I’ve trained in Italian cuisine both in Japan and in Italy, so anything I create through my filter is 100% Italian!” My love for Italy, the time I spent there, and the moments when I can communicate with Italian-speaking customers in Japan all reinforce my pride in being an “Italian chef.”

Always Seeking Exciting Environments

Even though I couldn’t speak Italian at the time, I thought, “If I can speak English, I’ll manage somehow!” So, I first enrolled in a sommelier school in Italy. During their training period, Italian chefs are called “stagisti,” or apprentices, and they learn while living and working in a restaurant.

Without any connections, I found out that my classmate Alessandro’s family owned a Michelin-starred restaurant. So, I asked him, “Can I stay at your place?” He replied, “There’s no room.” I pleaded, “I don’t care, even a barn will do!” He said, “I’ll ask my mom.” Eventually, they renovated a barn for me to stay in (laughs).

I stayed for about four months during the busy summer season in Liguria, a coastal tourist area on the west side of Italy, bordering France. As the off-season approached in the fall, and I had become fairly proficient in Italian, Alessandro’s mother, Signora, suggested, “Yoshi, next, you should go to the Piedmont region from fall until the snow piles up deeply. You’ll learn a lot because they use plenty of white truffles and porcini mushrooms.” She even helped me secure my next job at another one-star restaurant.

Starting with Signora’s introduction, I spent time in various places, becoming fluent in Italian. Then, I devoured restaurant books and Michelin guides from all over Italy and began calling up restaurants that interested me. “I don’t need a salary, do you have a room available?” “Is there a Japanese person working there? When will that person leave? I’ll take that spot!”

I have a strong desire to study whatever piques my interest and to dive headfirst into challenges. And once I feel I’ve mastered something to a certain extent, I often feel I’ve “cleared” that level and start seeking the next challenge. That’s a significant reason why I trained in eight different regions of Italy.

I might be more proactive and hyperactive than most people, but at that time, the strategy of cold-calling restaurants was standard. Everyone enhanced their experience that way. And thanks to the Japanese chefs who had ventured overseas before me, there was already a strong reputation for “Japanese” chefs, which was incredibly important.

The Continuing “Okuno-ism”

One of the challenges I want to take on next is “breaking down the traditional Japanese craftsman structure.” I’m not talking about the master-apprentice relationships within the industry. Do you know how many restaurants superstar chefs like Alain Ducasse, Joël Robuchon, and Alain Passard have around the world? It’s in the triple digits—100, 200 or more. Naturally, this means that the chef is not always physically present at each of their restaurants. Yet, customers still leave satisfied, saying, “Robuchon’s restaurant was amazing.” And if they happen to meet him, they feel “incredibly lucky.”

Overseas, there’s a widely accepted view that a super chef can also be a businessman, and there’s a depth of understanding among customers who nurture the restaurant. On the other hand, in Japan, where many restaurants, like sushi bars, have a small counter seating, the absence of the “taisho” (the head chef) has a significant impact. Customers might say, “I won’t go because the taisho is off today,” or “It’s different when the taisho is making the sushi.” While this sense of familiarity is part of the charm, I feel that sometimes customers themselves are missing out on the opportunity to see the taisho’s excellent skills passed on to younger or new talents.

Additionally, when an owner-chef expands their business, they are often accused of “chasing after money.” But what if that’s actually an investment in their future dreams? Perspectives vary. That’s why I want to break the structure that says, “A chef must be in the kitchen.” Expanding the number of restaurants shouldn’t automatically be associated with big chain restaurants; even high-end restaurants should be able to expand. I wonder if something might change if I can demonstrate this and gain recognition from the outside.

To achieve this, I’m actively involved in activities beyond just cooking, including training the next generation, consulting, and expanding restaurant operations. This is because I’m the type of person who rarely says “no.” I immediately respond with, “Oh, I’ll do it.” And instead of thinking, “Oh no, my workload has increased,” I think positively, “I’m so happy to have this much work!” That’s a big part of it. Right now, I’m doing consulting work in Thailand, and it looks like I might have some opportunities in Cambodia as well, so I’m looking forward to pursuing those with excitement.

DK Sugiyama is a powerful, sincere, passionate, and talkative person. His energy really pushed the interview forward, and before I knew it, it was over. I was surprised at how much of my own thoughts and ideas were drawn out, and I learned a lot from being able to see myself from an objective perspective. It was truly a wonderful time that allowed me to rediscover myself. Thank you very much!

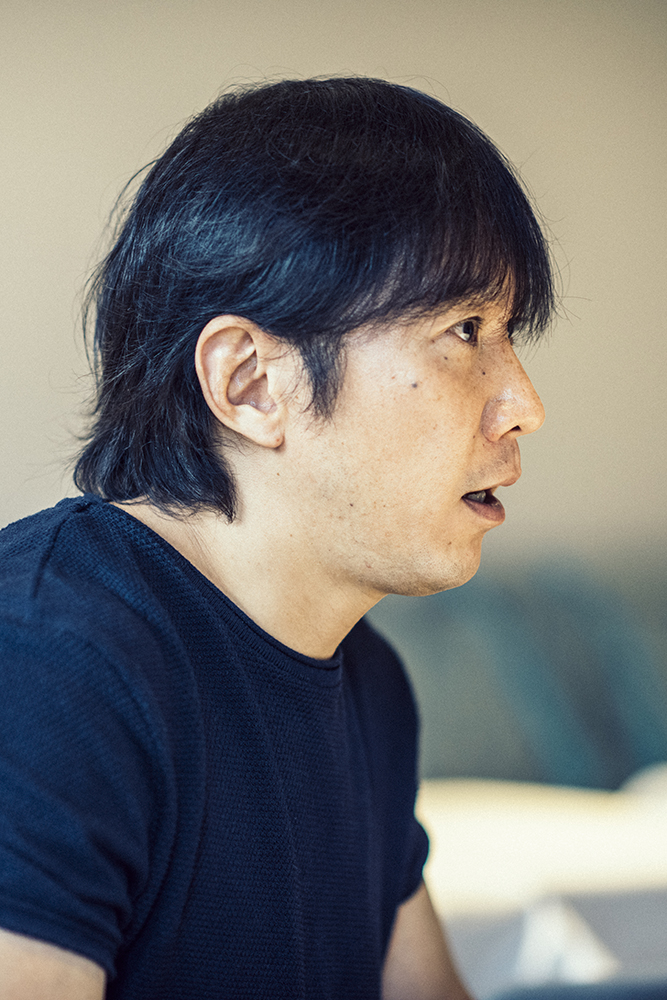

Owner-Chef of Ristorante La Brinca, Yoshiyuki Okuno

The one-on-one interviews with individuals who I am interested and curious about are the highlight of “My Philosophy.” I felt that Chef Yoshiyuki Okuno’s intense gaze and bold approach to life are truly reflected in the dishes he creates.

Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to visit Ristorante La Brinca, thanks to a senior from my university who took me there. It all began when I was introduced to Chef Okuno, and we discovered that we had many mutual acquaintances. The food was incredibly delicious, and the most memorable part for me was the knife with the sharpness of a surgical scalpel. While there are numerous media articles about Ristorante La Brinca and its cuisine, I was particularly interested in uncovering how Chef Okuno came to be and his thoughts as an owner, which were revealed during this interview. He is a man of remarkable drive. I look forward to visiting the restaurant again.

July 2017 at Ristorante La Brinca. Translated by ILI Inc.