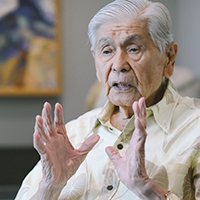

The single character "菓" prominently displayed on the paper bag is striking. Originating from Hakata, the traditional Japanese confectionery from Suzukake has now gained nationwide recognition as a popular gift. With overwhelming creativity that captivates people of all ages, what are the roots of their confectionery making and store creation that draw lines of customers to their shops? We spoke with Mr.Narimasa Nakaoka, the third-generation owner, about the secret behind their popularity and how their confectionery reflects the current era.

Profile

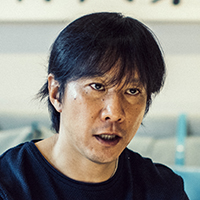

Vol.65 Narimasa Nakaoka

President and Representative Director, Suzukake Co., Ltd.

Born in Fukuoka Prefecture in 1969. After training at a confectionery shop in Osaka, he joined Suzukake Co., Ltd. in 1991. In 2010, he became the President and Representative Director. While inheriting the techniques and flavors of his grandfather, Saburo Nakaoka, who was honored as a "Contemporary Master Craftsman," he continues to pursue the inherent beauty of confectionery through his unique sensibility.

Suzukake Website:

http://www.suzukake.co.jp/

Please note that titles and positions are as of the time of the interview (August 2017).

Unforgettable Taste Memories

The first wagashi (Japanese confectionery) I ever tasted was a daifuku made by my grandfather, the founder of Suzukake, when I was just old enough to remember. Our home, the store, and the workshop were all located on the same premises. I vividly recall the gentle, indescribable scent of azuki beans being cooked that would greet me when I came home, the soft texture of the daifuku I would sneak from the workshop, the natural sweetness of the mochi itself—not just the red bean paste—all these aromas and textures combined to form my memory that “wagashi is delicious.” It was truly amazing.

Later, I went to train for two years at a wagashi shop in Minoh City, Osaka. It was a small shop where the father would make the sweets in the back, and the mother would sell them at the front. My memories from childhood came flooding back as I trained, reminding me of how my own family’s shop was like that.

However, when I returned to my family’s shop in Fukuoka after my training, I noticed that the taste of the daifuku had changed from what I remembered. When I asked why, I found out that adjustments had been made to prevent the mochi from hardening. At that time, the market for souvenir sweets was expanding rapidly, so sugar was added to the mochi to extend its shelf life and increase productivity. Traditionally, daifuku is made by wrapping the paste in freshly pounded mochi, which naturally hardens after a day. But the daifuku made with sugar-added mochi was noticeably different from the ones I used to find so delicious. This difference caused a bit of discomfort for me, as someone who cherished my grandfather’s original taste.

However, my father, who was the second-generation head of Suzukake at that time, and the craftsmen knew that freshly pounded mochi was undeniably the best. Even as he said, “This is the way of the times,” my father understood the importance of the traditional method. So I decided to return to that original recipe. The taste we recreate at Suzukake today is the same taste I memorized with my childhood palate.

Creating What is Expected in the Expected Way

Amidst a time when souvenirs and gift items were in high demand, I wanted to return to a more labor-intensive process to ensure that everyone could feel the genuine “deliciousness” of our products. Therefore, aside from Suzukake, I opened a shop called “Rin” in a small five-shaku (around 150 cm) showcase space at a local department store, where I only offered eight kinds of freshly made morning sweets that I personally loved. These sweets were made in the morning and sold on the same day, adhering to the traditional style. Only the head craftsman was entrusted with making these sweets to maintain their quality.

Every morning, I would personally take the sweets to the shop and stand there, eager to convey my passion for the products directly to customers. At first, there were complaints, such as, “The daifuku gets hard!” To this, I would explain, “These are made with freshly pounded mochi, so they are best consumed within a day,” and, “If they become hard after a day, you can toast or pan-fry them for a different but enjoyable taste.” Over time, customers began to appreciate the unique deliciousness of the “Rin” sweets. There was no grand strategy, and there was a real risk that they might not sell at all, but I had confidence that this way was simply more delicious. I was also deeply motivated by the desire to bring joy to our customers. After all, we are a manju (sweet bun) shop. Our primary focus must be on making the most delicious manju.

In the beginning, we had little money, so we designed and built the showcase ourselves out of white wood, and even made the plates for serving the freshly made sweets. I found the sight of the sweets placed in wooden and earthenware vessels to be beautiful. Everything was bare, unwrapped. Instead of selling pre-packaged souvenirs where the contents were hidden, I wanted customers to see and choose the products themselves and enjoy them first. I believed that gifts naturally followed from this process. Therefore, the sweets were displayed openly.

I also arranged flowers myself, though in a rather spontaneous way, to bring a sense of Japan’s four seasons into the shop, as wagashi are deeply tied to the changing seasons. I hope that our sweets can provide a small moment of solace, allowing people to savor the season and feel a little richer in spirit, even though sweets are not a necessity like the three daily meals. I also want Suzukake’s shops to embody this sentiment.

The first shop I created, “Rin,” embodies my thoughts on sweets and has left its mark on all seven of our stores nationwide. Each store has a five-shaku space, just like the “Rin” store, where seasonal flowers are arranged to welcome customers. The flow begins with customers sensing the season through the flowers before they choose their sweets.

No machines are used; even in department stores, our craftsmen handcraft the sweets at the back of the store and display them at the front. Customers can see this process through the glass. Just like in my childhood home and the shop in Osaka where I trained, we take the time and care to make everything properly on the spot. I believe that this attention to detail is what leads to both deliciousness and beauty.

Striving to Be Everyday Luxury

Sometimes, people think we are incredibly meticulous in our product and store creation, but the truth is, our approach might be best described as not being overly meticulous. For example, the boxes we use for our fresh sweets are quite simple. For items purchased for home use or as small gifts, I believe it’s better if there’s no extra cost for the packaging. For gift purposes, we offer carefully crafted bamboo baskets. We make a clear distinction between what is to be kept and what is to be discarded, allowing our customers to make their choice.

The seasonal wrapping paper is painted by a Japanese painter we have a close relationship with, and the large plates used to serve sweets in the store are made by a potter from Saga with whom we have long-standing ties. The architects who design our shops, the lacquer artist from Kanazawa who created our signs, and many others are all involved in what makes Suzukake what it is today. Often, ideas that we find intriguing during casual conversations with these creators and artisans take shape and become part of Suzukake. I believe that my own tastes and preferences act as a filter through which these creations come together to form Suzukake. However, I don’t think the name “Suzukake” needs to stand out. Our shop signs, paper bags, and the store name aren’t designed to be prominent. Instead of recognizing Suzukake by its name on a sign, it’s more meaningful to me if people sense the store’s atmosphere and say, “This must be Suzukake.”

Recently, we’ve had more opportunities to introduce Suzukake’s wagashi overseas, and wherever we are, we strive to use local ingredients and create sweets that suit the local lifestyle, all while maintaining the sensitivity of Japanese craftsmanship. Often, beautifully crafted traditional wagashi are introduced as representative of Japanese sweets, but that’s not all there is to it. There’s nothing wrong with pairing wagashi with champagne instead of matcha. Whether it’s traditional sweets, daifuku, or botamochi, made with local ingredients overseas, the idea is to create something properly, something that, when enjoyed in daily life, brings a sense of comfort and richness. I think that is true beauty—something akin to “everyday luxury.”

This philosophy applies not only to the creation of sweets but also to the way we build our stores. Even as times change, I want to continue making delicious sweets that people can’t help but sneak a taste of.

Meeting with DK Sugiyama made me reaffirm the importance of having the courage to take action. Traditional culture as we know it today is the result of accumulated changes over time. “Nothing starts if you don’t move! Nothing changes!” I was inspired by the powerful energy he exudes, which invigorates everyone around him, and it motivated me to keep challenging myself even more in the future. It was a delightful time. Thank you.

Narimasa Nakaoka, President and Representative Director, Suzukake Co., Ltd

After tasting the sweets from Suzukake that were given to me as a gift, I felt a resounding “Wow!” and immediately wanted to meet with President Narimasa Nakaoka. I quickly contacted the company and headed to Fukuoka, where he graciously agreed to appear in My Philosophy. When you want to meet someone, you’ve just got to make it happen! (laughs). And for that, you need to take action! Nakaoka-san is a man of both great heart and presence. His ability to delve into the essence of things and his constant drive for creative innovation embody the spirit of Japanese craftsmanship. If you can’t make it to their main store in Fukuoka, be sure to visitSuzukake in Isetan Shinjuku.

DKe Sugiyama Editor-in-Chief, My Philosophy

August 2017, at Suzukake Co., Ltd.Translated by ILI Inc.