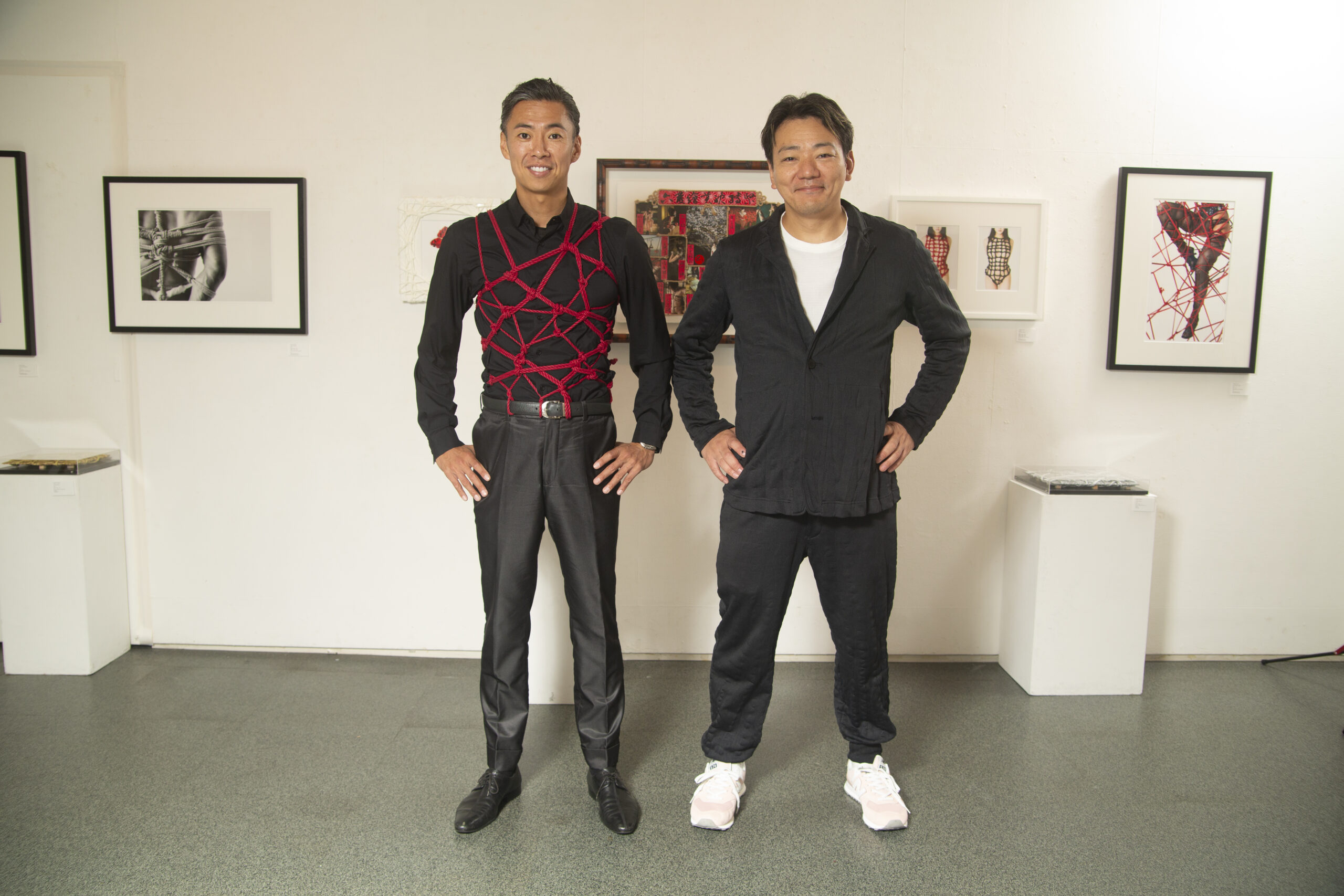

The first person in the world to recognize rope as an “art form” is Kinoko, Japan’s leading rope specialist. His work goes beyond tying people—he also ties trees, rocks, and even entire natural or architectural spaces. Renowned for his distinctive artistry, his creations have gained high acclaim in cities around the globe, including Paris, London, Sydney, Melbourne, Bangkok, Taipei, and Shanghai. Kinoko believes that “rope is like a tin-can telephone, linking you to the other person.” How did these works, which embody so many different kinds of “connection,” come to be? We spoke with him to find out.

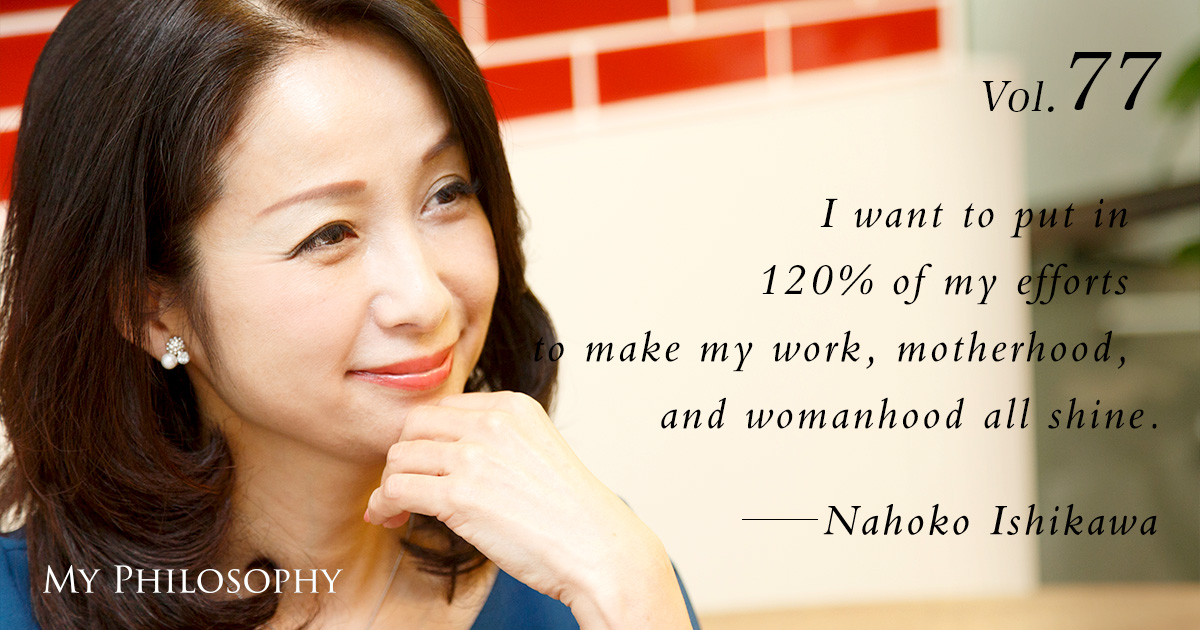

Profile

Vol.116 Hajime Kinoko

Modern Artist, Kinbakushi (Rope Master), Rope Artist, Photographer

Born October 22, 1977. In 2001, after discovering that his then-girlfriend enjoyed rope bondage, he began studying on his own under the mentorship of Yumeko. He later continued his training, taking lessons from Haruki Yukimura and Kannagi, whom he considers his esteemed teachers.

He reinterprets rope bondage beyond mere eroticism—sometimes with a pop flair or elevating it to art. He’s especially known for tying not just people but also elements of nature (trees, rocks, etc.) and entire spaces, earning him acclaim for his distinctive approach. In recent years, he has been actively showcasing art through photography and video, handling every aspect of tying, shooting, and directing.

Along with domestic performances, he has appeared and conducted workshops in around 30 locations worldwide—including Paris, London, Rome, Berlin, Sydney, Melbourne, Vancouver, New York, Los Angeles, Taipei, and Shanghai—and his recognition overseas continues to grow. He is regarded as one of Japan’s foremost rope specialists.

Hajime Kinoko Shibari and Rope Bondage Official Home Page

https://shibari.jp/

Instagram

https://www.instagram.com/hajime_shibari/

Pursuing “Connection” ― The Origin and Philosophy of an Artist

When people hear “rope bondage,” many may associate it with SM. But for me, rope is not just a tool. I use it to design spaces, create body designs like knitting, tie up buildings, craft stage sets and playground equipment for children…

Rope is “art,” and its possibilities are boundless. There was even talk of tying up the entire Roppongi Hills complex once, although that turned out to be impossible.

There’s a mysterious power in tying. Some people say they feel liberated, and others, perhaps due to a rush of adrenaline, feel energized. Surprisingly, many people also get sleepy. It could be similar to the sense of security a baby feels while protected inside its mother’s womb.

That’s why, the very first time I tie someone, I feel a huge sense of responsibility. I always try to do it in a way that benefits that person. If I look at someone and think, “They seem tired,” or “They want to be treated gently,” I’ll tie them gently, at their own pace. If I notice “They’ve had something unpleasant happen,” I try to help them reset, even just a little.

I tie in sync with their pace. When another person is involved, each time I create a one-of-a-kind piece that is perfectly matched to them.

When people hear “rope bondage,” many may associate it with SM. But for me, rope is not just a tool. I use it to design spaces, create body designs like knitting, tie up buildings, craft stage sets and playground equipment for children…

Rope is “art,” and its possibilities are boundless. There was even talk of tying up the entire Roppongi Hills complex once, although that turned out to be impossible.

There’s a mysterious power in tying. Some people say they feel liberated, and others, perhaps due to a rush of adrenaline, feel energized. Surprisingly, many people also get sleepy. It could be similar to the sense of security a baby feels while protected inside its mother’s womb.

That’s why, the very first time I tie someone, I feel a huge sense of responsibility. I always try to do it in a way that benefits that person. If I look at someone and think, “They seem tired,” or “They want to be treated gently,” I’ll tie them gently, at their own pace. If I notice “They’ve had something unpleasant happen,” I try to help them reset, even just a little.

I tie in sync with their pace. When another person is involved, each time I create a one-of-a-kind piece that is perfectly matched to them.

Technique and Expression ― Japanese Aesthetics and a Unique Style

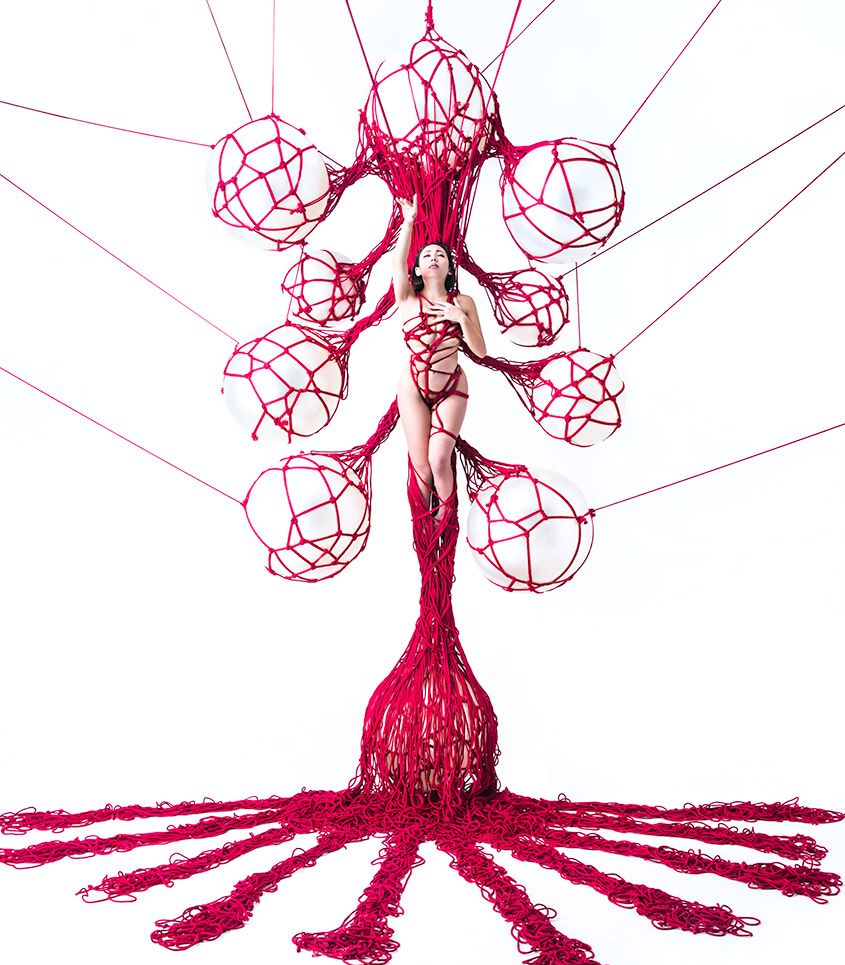

Tree of Life 2018 ED.5 pigment print・crystal paper Photo by Hajime Kinoko Rope by Hajime Kinoko

My encounter with rope happened purely by chance. One day, a senior colleague told me, “Hey, go manage this fetish bar in Roppongi (a place where people with various fetishes gather).” I ended up dating a woman who identified as M there. Then, one day, an older woman suddenly came into the bar. She said, “If you’re running a fetish bar, you at least need to know rope bondage. Learn it!” That’s how I started learning tying techniques. Later on, I found out that my senior colleague had sent that woman, Yumeko-shi, to teach me. She later became my mentor. It was like receiving an intensive SM education (laughs). As I started getting a bit more competent, I asked her one time, “Do you want me to tie you?” She immediately refused: “No need.” She told me, “It’s because you want to tie, not because I want to be tied. It’s meaningless if it’s not coming from a place of your own desire.”

This experience led me to realize the essence of “connection” in tying. Rope is like a tin-can telephone, linking you and your partner together. It’s not just about a physical link, but also a heart-to-heart connection. It’s a true conduit.

My technique naturally developed from tying about ten customers a day at the bar. I really took notice of my skill level one day when I brought performers to do rope shows at the bar. During the rope scenes, for some reason, the audience all started falling asleep. I wondered, “Why?” Then I watched the show… and it was really bad. So boring that I couldn’t believe they charged money for it.

When I saw an SM competition at a strip theater located a few doors down from our bar, I again thought, “I’m better at rope than these people.” Yet those people also called themselves professional “kinbakushi” (rope masters). So I figured, “Well, I’m just an amateur, but I’d like to try performing in a show once,” and asked some connections to introduce me. I actually performed in a show, had a great time, and I’ve been doing it ever since.

As I started getting a bit more competent, I asked her one time, “Do you want me to tie you?” She immediately refused: “No need.” She told me, “It’s because you want to tie, not because I want to be tied. It’s meaningless if it’s not coming from a place of your own desire.”

This experience led me to realize the essence of “connection” in tying. Rope is like a tin-can telephone, linking you and your partner together. It’s not just about a physical link, but also a heart-to-heart connection. It’s a true conduit.

My technique naturally developed from tying about ten customers a day at the bar. I really took notice of my skill level one day when I brought performers to do rope shows at the bar. During the rope scenes, for some reason, the audience all started falling asleep. I wondered, “Why?” Then I watched the show… and it was really bad. So boring that I couldn’t believe they charged money for it.

When I saw an SM competition at a strip theater located a few doors down from our bar, I again thought, “I’m better at rope than these people.” Yet those people also called themselves professional “kinbakushi” (rope masters). So I figured, “Well, I’m just an amateur, but I’d like to try performing in a show once,” and asked some connections to introduce me. I actually performed in a show, had a great time, and I’ve been doing it ever since.

More “Chef” Than “Artist” ― A Style That Stays Close to the Other Person

White 2018 ED.5 pigment print・crystal paper Photo by Hajime Kinoko Rope by Hajime Kinoko

I’m not really aiming to destroy tradition; rather, I want to preserve it. I’ve heard a story where someone was excommunicated from the tea ceremony world for an expression like “smashing the tea bowl,” but in my case, I don’t put myself at the center. I focus on group-oriented expressions that help things flow around me. “Connection” is truly about staying close to the other person. That is my philosophy. My signature “-Red-” series also revolves around this theme of “connection.” The red rope used in my pieces symbolizes things like blood and the fateful red thread that ties us together. That’s why I feel I’m closer to a “chef” than an “artist.” An artist often makes whatever they want and looks for people to agree with it, while I prefer to stay close to the other person, listening to their requests and then incorporating 80–90% of my own ideas—what I want to do and what I think looks cool—while adapting it to that individual.An Installation by Hajime Kinoko Appears at the Sand Court in Miyashita Park!The piece in Shibuya’s MIYASHITA PARK originally came from the theme of collaborating on Taro Okamoto’s work “Myth of Tomorrow.” That piece features a nuclear bomb in the center, people lined up covered in blood, and these little bugs representing “My Little Stars.” However, along the way, that plan fell through. So instead, I decided to express hope. Japanese rope bondage has a special quality in the eyes of the world. Japanese erotic expression often has very intricate, even obsessive settings. The scenery glimpsed through a gap in a sliding door, the steam rising on a cold day, the slightest tremor… This meticulous attention to detail is what raises rope bondage to the realm of art. All Japanese arts contain a concept of “shingyōsō” (new forms). In calligraphy, you progress from kaisho (block style) as the “form,” gyōsho</> (semi-cursive) as the “phase,” and sōsho (cursive) as the “final form.” Each stage is a new expression. It’s the same with architecture, tea ceremony, and ikebana (flower arrangement). You have to learn the standard forms and master the basics before you can freely break them. So, first comes the form. You can’t break form if you don’t know it. For that reason, I have created rope-bondage dojos around the world, establishing a standard. Like ikebana or kendo, I introduced a grading system for kinbaku. Beginners start at 10th kyu, advancing until they reach 1st kyu and then moving on to the dan ranks. You learn 91 fundamental techniques from video materials and master them one by one. Only then can you open the door to free expression. So far, I’ve taught in 30 countries and regions around the world.

Connecting People ― Performances and Beyond

For a show, I think what’s most important is reading your partner’s reactions. When I stand behind them, I can sense their state from the feel of their body or the way they move their hands. It’s like a sort of statistics: you quickly pick up on how people react.

Because tying can be quite dangerous, I’ve studied human anatomy in detail, such as the location of nerves. I also hold the necessary qualifications to suspend people.

When deciding on a theme for a show, I choose something I think is cool, and also something the audience can truly enjoy and get immersed in. There’s an experimental side to it, as I try out new things and gradually improve my technique. I align my performance with the music’s tempo, incorporating tension and release to synchronize with my partner’s breathing. Sometimes the audience is so moved, they shed tears.

When you use something for a long time, its essence becomes clearer. Through rope, I can feel the other person’s breathing, body heat, degree of tension, skin texture, muscle tone, and even bone position. It’s something you only gain from hours of direct contact with rope. It’s like someone who’s used chopsticks for so long they can tell just by touching whether food is soft or firm, or even if it’s something they enjoy. It’s that kind of sensitivity.

The more strongly you think of the other person, the more you can feel through the rope, and you can tie them in a way that truly meets their needs.

With the internet so widespread, I feel people are starting to forget the true meaning of touch and connection. But I hope my work helps people remember those important figures and moments in their lives. Mothers, ancestors, nature, friends, DNA, the future, heart-to-heart bonds―I want to express all kinds of connections.

In the past, Japanese culture saw beauty in the scenery glimpsed through a tiny gap in a sliding door, or in the way steam rises on a cold day. This rope art, born from such a delicate aesthetic sense, is what I want to bring to modern times and expand into new territories. That’s my mission.

From here on, I want to try unknown, uncharted things. I value every single encounter, continuously searching for new means of expression.

I also hope the rope-bondage community itself finds a proper footing here in Japan. In reality, many people who shape our world are quite open-minded about it, but those just below them are still not so accepting. I want to touch people’s hearts and move them, through the rope. That journey is never-ending.

For a show, I think what’s most important is reading your partner’s reactions. When I stand behind them, I can sense their state from the feel of their body or the way they move their hands. It’s like a sort of statistics: you quickly pick up on how people react.

Because tying can be quite dangerous, I’ve studied human anatomy in detail, such as the location of nerves. I also hold the necessary qualifications to suspend people.

When deciding on a theme for a show, I choose something I think is cool, and also something the audience can truly enjoy and get immersed in. There’s an experimental side to it, as I try out new things and gradually improve my technique. I align my performance with the music’s tempo, incorporating tension and release to synchronize with my partner’s breathing. Sometimes the audience is so moved, they shed tears.

When you use something for a long time, its essence becomes clearer. Through rope, I can feel the other person’s breathing, body heat, degree of tension, skin texture, muscle tone, and even bone position. It’s something you only gain from hours of direct contact with rope. It’s like someone who’s used chopsticks for so long they can tell just by touching whether food is soft or firm, or even if it’s something they enjoy. It’s that kind of sensitivity.

The more strongly you think of the other person, the more you can feel through the rope, and you can tie them in a way that truly meets their needs.

With the internet so widespread, I feel people are starting to forget the true meaning of touch and connection. But I hope my work helps people remember those important figures and moments in their lives. Mothers, ancestors, nature, friends, DNA, the future, heart-to-heart bonds―I want to express all kinds of connections.

In the past, Japanese culture saw beauty in the scenery glimpsed through a tiny gap in a sliding door, or in the way steam rises on a cold day. This rope art, born from such a delicate aesthetic sense, is what I want to bring to modern times and expand into new territories. That’s my mission.

From here on, I want to try unknown, uncharted things. I value every single encounter, continuously searching for new means of expression.

I also hope the rope-bondage community itself finds a proper footing here in Japan. In reality, many people who shape our world are quite open-minded about it, but those just below them are still not so accepting. I want to touch people’s hearts and move them, through the rope. That journey is never-ending.

Rope Artist Hajime Kinoko

October 2024, at art space kimura ASK? Interview & Editing: DK Sugiyama Project Manager: Chiho Ando Text: Eri Shibata (Deputy Editor-in-Chief, “My Philosophy”) Photography: Erina Hamaya