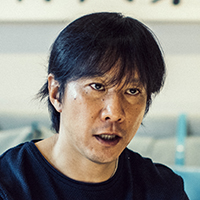

Tomizo Yamaguchi, the third-generation head of the long-established Kyoto confectionery “Suetomi,” founded in 1893 (Meiji 26). As a successor of the traditional Kyoto confectionery craft and spirit, he reflects on the fading essence of the Japanese heart.

Profile

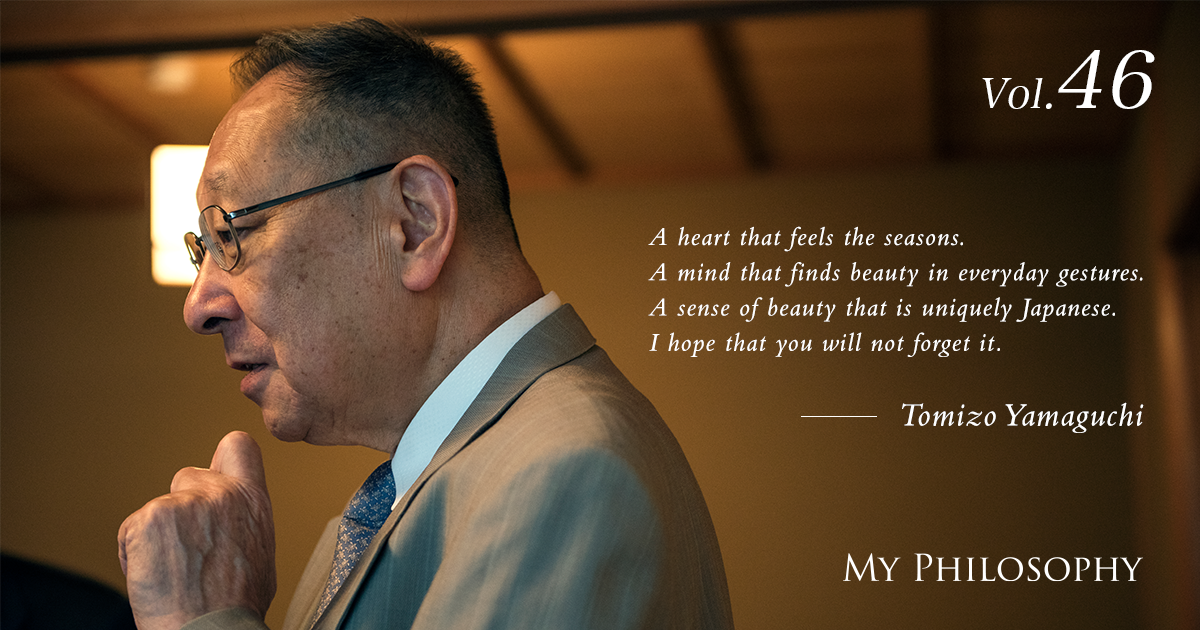

Vol.46 Tomizo Yamaguchi

Third-Generation Head of Kyoto Confectionery "Suetomi"

Born in Kyoto Prefecture in 1937, Yamaguchi graduated from the School Faculty of Economics at Kwansei Gakuin University. He serves the tea ceremony grand masters and various temples and shrines in Kyoto. While inheriting tradition, he has also pioneered a new realm of Kyoto confections, creating innovative sweets inspired by classical music. Yamaguchi is active in a wide range of fields, including television, newspapers, magazines, and public lectures across the country, conveying the essence of Japan through Kyoto confectionery.

His published work includes "Kyoto Confectionery World of Suetomi (Kyo Kashi Tsukasa Suetomi Kyogashi no Sekai) (published by Sekai Bunka Publishing). For more information,

visit the Suetomi website.

*Titles and positions are as of the interview date (July 2016).

Kyoto Confections with an Open-hearted Spirit

In Kyoto, when welcoming guests, it is customary to always prepare sweets and tea. Kyoto’s confectionery world is divided into two realms: the realm of the confectioner (kashiya) and the realm of the everyday sweets seller (oman-ya-han). The oman-ya-han deals in everyday snacks, while the kashiya handles both formal confections (jōnamagashi) and dry sweets (higashi) meant for hospitality. While there are specialty stores for dry sweets, a kashiya must be adept at both. When sweets are served in Kyoto, don’t hesitate—express how delicious they look and eat them quickly, as they lose their flavor once they dry out.

Edo (Tokyo) confections are delicate and realistic in appearance. Although it might sound harsh, Kyoto’s approach is broader and more open-hearted. For instance, Tokyo’s “uguisu” (Japanese nightingale) shaped sweets have sesame seed eyes and intricately shaped wings, while Kyoto’s version is simply a pinched piece of mochi. When “uguisu” Kyoto confections are made to look realistic, they might be described as “mossari shiteiru” (a bit clumsy).One can see the slight resemblance to an actual uguisu. Additionally, while Tokyo confectioners often add a pinch of salt to their sweet bean paste, Kyoto’s confectioners never do. Moreover, unlike Western sweets, Kyoto sweets typically don’t include added fragrances. The basic ingredients are red beans, sugar, and rice, emphasizing the natural flavors. Although natural elements like mugwort may be used to add seasonal scents, using artificial fragrances is considered unconventional. Nowadays, matcha (green tea) sweets are popular, but the prevailing belief in Kyoto is that tea-flavored sweets are unsuitable because they interfere with the taste of the tea being served.

The Era When Sugar Could Not Be Freely Traded

Confectioners have historically operated as servants to the aristocracy and high-ranking individuals. As a result, they had to cater to their customers’ demands, but in return, they were allowed to use white sugar, which was controlled by the shogunate. Sugar was introduced to Japan during the time of Oda Nobunaga. Back then, sweet treats were extremely expensive and beyond the reach of ordinary people. It was likely not until the Meiji era that sweets became accessible to the general public. I still remember the time during the war when there was no sugar. There was no sugar in the rations, and people queued up to buy sweets made with artificial sweeteners like saccharin and dulcin.

During the war, all confectionery shops in Kyoto closed down. Confectioners were drafted into military factories and could no longer continue their trade. Suetomi, being a purveyor to the Higashi Honganji Temple, managed to receive some sugar from the Army Ministry to produce offerings for the spirits of the war dead. Due to economic controls, sugar could not be freely traded until around 1951. Despite experiencing a time when we couldn’t consume sugar, it’s remarkable how we survived. When I was little, the workshop was piled high with sugar, and I often got scolded for digging tunnels in it. I’m probably the last one who remembers what Kyoto’s confectioners were like before the war, over seventy years ago. In those days, those who could afford to eat sugar were considered privileged and boasted about it. Nowadays, people claim that sugar is bad for health, but they don’t understand its true value. Sugar is delicious, and this appeal is universal and eternal.

Learning from Customers

Until recently, the sweets served at tea ceremonies were ordered by the wives of the tea masters. I would bring samples to them, and we would discuss the options across the kitchen table. Sometimes, I’d be scolded with remarks like, “This won’t do at all.” I learned the art of confectionery from this world. When I took over the shop, I once received an order for a thousand sweets for a tea ceremony. Fearing I wouldn’t meet the deadline, I prepared them the day before, but they became hard. I was reprimanded by the customer: “Guests will only eat these hardened ones!” This experience taught me that confectionery making is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Thankfully, I wasn’t told, “We’ll never use your shop again!” Instead, they said, “You need to be more careful from now on!” They continued to patronize our shop and taught me many things.

In business, one must learn by connecting with people. I believe that being strictly guided by customers and blessed with good people was more beneficial than learning from my father. In Kyoto, confectioners cannot simply make sweets and wait for them to sell. Delivery and interaction with customers are crucial for learning and improvement. It’s vital to be proactive and engage with customers, rather than passively waiting for sales. Movement and interaction through people are what drive business.

The Changing Aesthetics of the Japanese People

Recently, yokan (sweet bean jelly) is mostly sold in bite-sized pieces. There used to be an aesthetic around how to thinly or thickly slice it, and how to cut it smoothly. This act of “cutting” had a unique beauty. I think Japanese people once appreciated such mysterious aesthetics, but these days, it seems to have faded away. Many people don’t even know how to sharpen a knife. At convenience stores, you can buy pre-cut cabbage, and there are probably many households without knives, where people don’t even know that cutting onions makes you cry.

The way of life in Japan has fundamentally changed. Although Japanese cuisine has been recognized as an intangible cultural heritage, the methods of making dashi (broth) have become homogenized. Various regions had their unique flavors, but now, people use the same instant dashi powder everywhere, which is not good. Even rice, which used to have distinct flavors depending on the variety, is now predominantly Koshihikari. Sweets have also become uniform in taste. There are more confectioners now who only do the final touches. How many shops in Kyoto still cook their own sweet bean paste? It feels like Japan as a whole is moving in this direction.

Another troubling trend is the obsession with “cuteness.” Nowadays, if something isn’t cute, it won’t sell. Everything has to be cute in appearance, color, and shape. There’s no room for anything else. The unique Japanese sensibilities of “having character” or “having charm” have disappeared. Japanese aesthetics are bound to change from here on. The absence of tokonoma (alcove) in homes is also changing the Japanese sense of beauty. People no longer feel the seasons by decorating with seasonal scrolls or flowers. The joy of imagining spring while appreciating the warmth of a single plum blossom and waiting with anticipation is fading away. It is sad to see such beautiful aspects of the Japanese heart disappear.

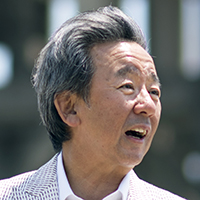

When I first met Mr. Sugiyama, I was amazed to see that such young people are leading the current Japan. In my daily work, I mostly interact with older individuals who can relate more to my lifestyle and thoughts. This time, after meeting Mr. Sugiyama and having a brief conversation, I was surprised to find that we share many similar views. This encounter has heightened my expectations for the future of Japan. I realize that I too must keep learning and studying.

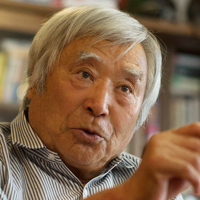

Tomizo Yamaguchi, Third-Generation Head of Kyoto Confectionery “Suetomi”

Suetomi Confectionery meticulously prepares all of its sweets from scratch, consistently offering genuine fresh confections and dry sweets. Each fresh confection weighs less than 50 grams, but once you understand the story behind its creation from concept to completion, you might find it almost too precious to eat. The enduring popularity of Suetomi’s sweets can be attributed to Tomizo Yamaguchi’s dedication to the spirit of Ichigo Ichie—treasuring each unique encounter.

Suetomi’s confections are available at Takashimaya stores. If you haven’t had the pleasure of trying them yet, I highly recommend you do so.

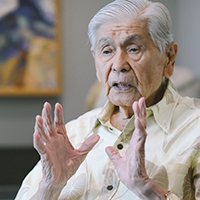

This interview with Mr. Yamaguchi, made possible by the introduction from a respected senior, marks the 46th installment of “My Philosophy.” Each encounter is truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Our initial goal was to reach 50 interviews in 10 years, and through each session, we have learned so much, filling us with gratitude. We cherish each meeting and look forward to continuing this journey.

July 2016,main store of Suetomi Confectionery.Translated by ILI Inc.